"The love from success is always temporary."

"Good for a Girl" is a pro athlete's remarkably candid memoir.

“I thought I was basically a guy, a freak superhero version of a girl, and I would improve every year until infinity.”

That’s the kind of quote I’ve come to expect from the ever-candid Lauren Fleshman. (You can read the context for it below.)

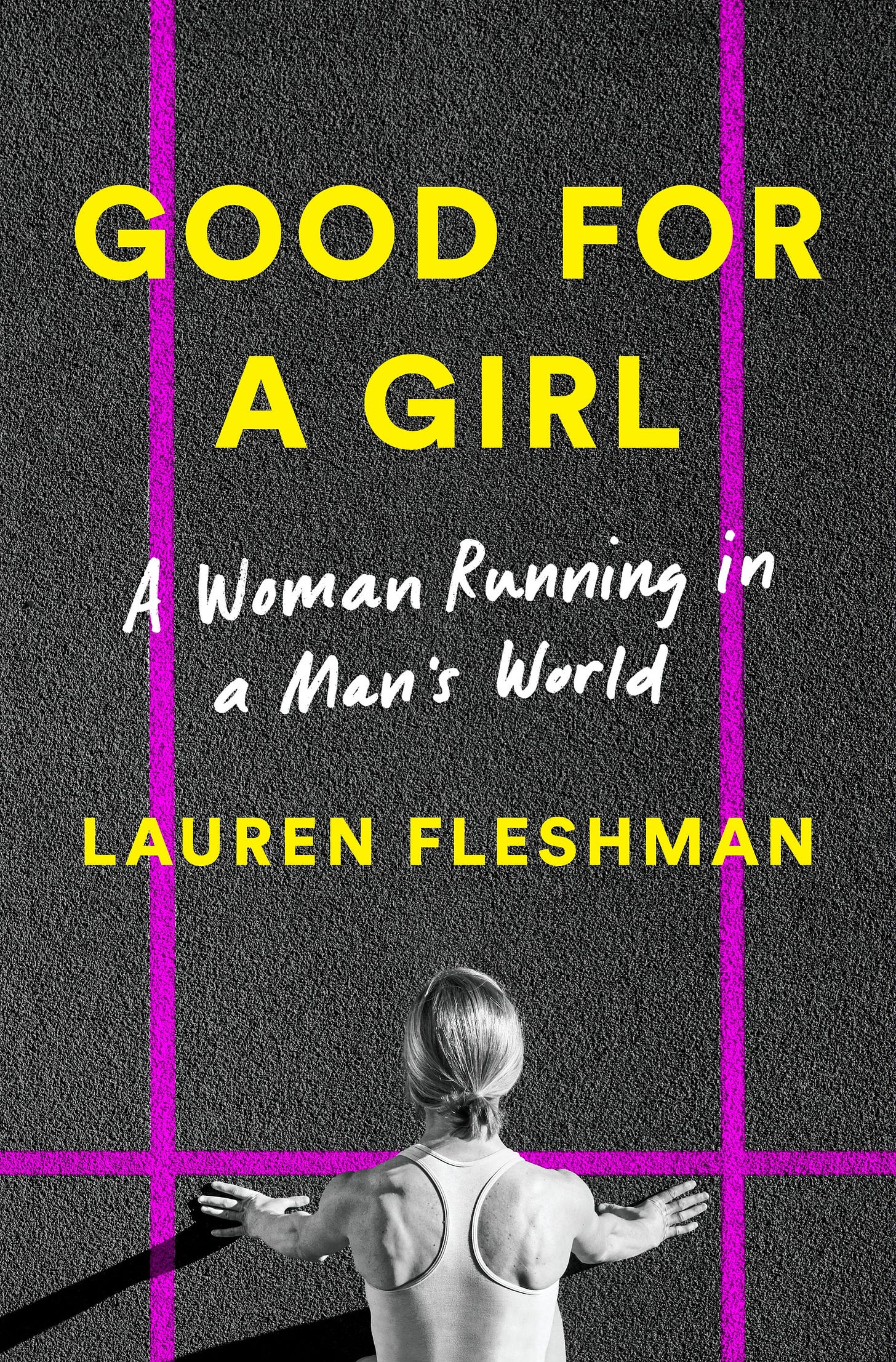

As a distance runner, Lauren was a five-time NCAA champion, and two time U.S. champion in the 5,000-meters (2006 and 2010). Today, she’s a coach, an entrepreneur (cofounder of Picky Bars), a brand strategy advisor for apparel company Oiselle, and now the author of the new book Good for a Girl. It’s a remarkably blunt memoir of her athletic development, as well as a treatise on female physiology.

As usual with Range Widely Q&As, this is longer than a typical post, so let’s get to it…

David Epstein: Early in the book you portray a scene where you’re coaching runners, and you say, flatly: “I don’t miss it — I had my turn.” Getting to as high a level as you did, I would imagine there are some things you miss about it. If so, what do you miss the most?

Lauren Fleshman: There are two things I do miss. I miss the feeling of being in absolute world-beating fitness, a feeling I had only a few weeks a year. I felt like a frothing bull for competitive opportunities, stood taller with a “bring it on!” attitude even when brushing my teeth, and was prone to grandiose ideas like “I could walk right up Everest right now if someone transported me there.” That was a fun feeling. And the other thing I miss is the travel without kids. The variety of cities and landmarks, both famous and obscure, but more than that, the space. All that time spent in airports and bus stops and train stations simply shrugging at a three hour layover because who cares? That’s probably more a sign of missing life before kids though haha.

DE: On that note, I’ve long admired your candor. You spoke to me openly, for instance, when I was investigating the Nike Oregon Project, about your misgivings regarding some medical treatment. So I was expecting frankness in Good For a Girl. And you delivered, so I want to go personal. On page one of chapter one, you write that your dad “was the kind of dad who wanted sons, but he got two daughters and refused to adjust his parenting plan.”

He was fiercely proud of you being an athlete (beating the boys in the gym class mile) and a hard-ass (he told his buddies that you had “balls the size of Texas!”) but you describe the situation for your mother in your home as “frozen in the 1950s.” You write about your father’s alcohol abuse, and that “Dad got the best chair, the first serving, and the last word. He told his daughters not to take shit from anyone, then turned around and treated my mom to large helpings of his own.” This kind of reminded me of when I read about surveys showing that men are more keen to have daughters who are strong and independent than wives who are strong and independent.

I knew plenty about you as a runner, but none of this. Why did you decide to include this material in the book?

LF: The themes and revelations of the book are contextual to the person I am and how I see the world. I needed people to know what made me such an observer, so hypervigilant, so bought into the patriarchal forces of women seeking the approval of men. I also needed them to see that these forces aren’t just relics of an older era cemented into a sports system. They are alive and well in many of our homes even now. They shape our choices, opinions, and biases long after we leave home and enter other environments until they are challenged. They live inside us. I wanted the reader to see how it came to live inside me, what the consequences were, and how I came to begin extracting them. In addition, the relationship with my father is an example of how sometimes the people who are the most empowering and loving are also the cause of our pain. That’s women’s sports, too.

DE: To me, this book is in many ways about adapting to change. On the physical side, some of those changes are volitional, like through training, and others not, like puberty.

It made me think back to my high school sports days. I played football, basketball, and baseball before getting into track, and I remember a football coach always asking me: “When are you gonna grow?” Turned out the answer was: “In my next life.” So it was the lack of change that was an issue for me. It brought me back to that feeling when I read the section in which you write: “I was developing an awareness that my trajectory of success in this sport I was falling in love with might not have been entirely within my control.” Can you expand on that?

LF: I feel for high school David. That’s analogous to my experience, really. It’s rather universal in a way, that tender time when you are waiting to see if your changing body is going to cooperate with your big dreams for your future. And that is out of your control. Sometimes genetics are simply not going to come through. But in girls’ sports there is this additional layer. We are counting people out because of a lack of education on the female body and mistakenly comparing it to a male standard of development. The most common puberty changes for young women are viewed as disqualifying from excellence, due to a lack of awareness about a typical female development timeline. Breasts, hips, increased body fat, on average these things are not immediately beneficial to sports performance, but after a period of adjustment, your woman body is ultimately your most powerful and excellent body. There is pressure to erase or reverse these changes through diet restriction. But we need to just chill. Girls just need to be given the encouragement and support to ride it out for a little bit. Instead, without education of sex-based differences, coaches and parents treat this short-term plateau as a sign of one’s ultimate potential. It’s ridiculous. It’s like taking a bunch of pubescent male singers and declaring who has long-term potential in the field of music at age 13. Collectively, we understand that males experience vocal changes around this age that are not indicative of anything except puberty is happening. If we encourage their love of music through the changes, they have an opportunity to blossom once again when they find their new voice.

DE: Fortunately for you, you did keep getting faster. But you note that “some girls ran slower despite training more.” You write memorably about Kim Mortensen, who — when you were a freshman in high school — set the national high school 3200-meter record. It stood from 1996 until 2018! Kim accepted a scholarship to UCLA, but soon took “medical retirement due to an eating disorder.” You suspected that Kim had been trying to “outrun puberty.”

She’s kind of symbolic in the book of this tightrope that female athletes walk between healthy eating and disordered eating. You note that a 2021 study of female distance runners (average age: 17) found that almost half weren’t getting normal periods, and around 40 percent had low bone density. We give a lot of lip service to sports being healthy, and they certainly can be, but I’m convinced that the benefits don’t just magically manifest if we don’t work to cultivate them. Can you talk a little about how you walked that tightrope with respect to food in your own career?

LF: For me, food started out as enjoyable and energizing and part of culture and connection and I didn’t think about it beyond that. Later, it became a tool for changing my body into something deemed better than the body I had, and that’s when rules came in, assigning moral value to different kinds of foods, calories were obsessively counted, and I got further and further away from connection to my own hunger and full cues and intuitive cravings. Elite women athletes have been fed this idea that there is an ideal body for excellence and it happens to resemble the male standard as closely as possible. It is a very narrow band. The truth is, there is a wider body diversity for high performance than we have been led to believe.

DE: One of the conundrums here is, I think, that disordered eating sometimes makes people faster in the short-term, because they lose weight quickly. To me, a major theme of my last book was that sometimes things that cause short-term boosts can undermine long-term development. But — human intuition being what it is — it’s hard to internalize the idea of a short/long-term tradeoff. So young runners who saw you racing, or saw Shalane Flanagan, or Jenny Simpson, or whoever, they probably just saw a very lean body and a lot of success, and their reflex might not be: “Well, they got that way over years, so let me take this slow.” So what can be done in this particular battle against human intuition?

LF: Raising consciousness about the female performance wave is a great start. We need to normalize the progression of the trained, developing female body from childlike to softer and fuller, to getting leaner with age. We also need to focus a lot of energy on protecting a healthy menstrual cycle. Young people do tend to respond best to short-term incentives and we need to hammer it home that a menstrual cycle is not about some distant future when you may want to grow a baby. It is an immediate sign of health and performance. Menstrual dysfunction decreases your pain tolerance, your recovery time, your immune system, and your bone healing. Any short term gain from altering your strength-to-weight ratio will be quite quickly reversed by missed time due to illness or injury. Nothing beats stringing together years of consistency in a healthy body.

DE: Turning to your college career, there’s a really memorable scene in the book from the end of your visit to Stanford. Basically you loved it, and decided you wanted to go there. And then you meet with coach Vin Lananna, who had turned Stanford into a national powerhouse, and he pulls a calculator out of his drawer and says: “Here’s what I can offer you right now,” in terms of a scholarship, and the calculator reads: zero. But then he says that some scholarship athletes are graduating soon, and “if you do well as a freshman,” he can offer you an 88% scholarship the next three years.

A bunch of colleges were offering you a full ride. For Stanford, you’d have to draw on family support, savings from working at In-N-Out, a campus job, and, as you write, “I’d be sneaking my roommates’ deodorant.”

So what’s it like to be such a terrible roommate? …Kidding! Ok serious question: that was a big “if” that Vin gave you. Given what you know about how quickly body changes can hamper a running career, how did you decide to bet on yourself in that situation versus taking the safe route of a sure scholarship?

LF: The truth is, I thought I was different, that I escaped the grim reaper. I thought that if puberty was going to get me, it would have got me in high school, and it didn’t get me then. I grew taller and stronger like a guy at first. I thought I was basically a guy, a freak superhero version of a girl, and I would improve every year until infinity.

DE: As it turned out, freshman year went well. You qualified for the Olympic Trials and broke the American junior record in the 5,000-meters the first time you ran it. So, yeah, you earned that scholarship. But a few paragraphs after you recount those triumphs, you’re writing about body changes. About your “thighs touching more” and your Levi 501s fitting differently. Everything is going great. You’re enjoying class; you’re social; you’re learning guitar and making art in the courtyard. As you put it: “I’d never felt so creative, playful, and embodied, like I was becoming who I was meant to be.” And then: “The only place I felt tension around my new body was in sports.”

I think sports are sometimes cast as the one place where girls and women don’t have to worry about their bodies, at least not in the typical way. But for you, it was the opposite. How did you deal with that, from a psychological and a performance perspective?

LF: Sport is hypothetically a place where we get to use our bodies in powerful ways that aren’t objectified and sexualized, a place just for us. But even that is compromised by our culture. Just look at NIL deals disproportionately rewarding physical appearance in women. Sports is very much a place where girls and women have to worry about their bodies…Entering that softer stage of development in running I felt slower, I lost my previous ease for a while. That made me resent my body, and fear it would never feel great and as powerful again. I wasn’t aware of the positives of simply moving through that stage of life without fighting against it, that my best years were waiting on the other side if I stayed healthy throughout it and kept my period.

DE: And ultimately, you recount that you did lose your period, and your bone density declined, and you got injured. …Shifting gears for a minute, let’s talk money. I like that you got into specifics in the book, because people don’t really know how that works for runners. Most of an runner’s money comes from sponsorship deals with apparel brands, so your livelihood can hinge on marketability rather than performance. I was really surprised to read that you decided, just out of college, to act as your own agent in discussions with Nike. Can you explain why you did that?

LF: I knew women’s sports were treated as second class across the board. I didn’t trust an agent (nearly all were men) to truly believe in the worth of female athletes and ask for enough money. I didn’t view myself as a typical woman, and felt I could best convey that in person to the executives. I had benefited from being viewed as one of the guys all my life, and I thought my best chance at a decent contract was making sure they viewed me like that too. Offers were coming in at the 30-40k per year range, whereas men with my resume would get over 100k, and a man with star power could get over 200k.

DE: That’s distance runners, but then there’s a really interesting scene at the World Championships where you’re talking to sprinter Jon Drummond, who was a lot more accomplished on the world stage than you were. Can you describe what happened there?

LF: He woke me up to the reality that there were different standards for sprinters, who were majority Black. Despite sprinters winning the vast majority of our medals and garnering all the star power on stage, many had contracts that were absolutely ruthless: win or starve. They had to win medals to keep a decent salary, and could go unsponsored even if they were top 10 in the world. Whereas for a white distance runner like me, whose identity more closely matched the white male distance runner executives, I was given a certain amount of value just for existing. I didn’t have to back it up with gold medals. Bonus points if you’re cute and blonde.

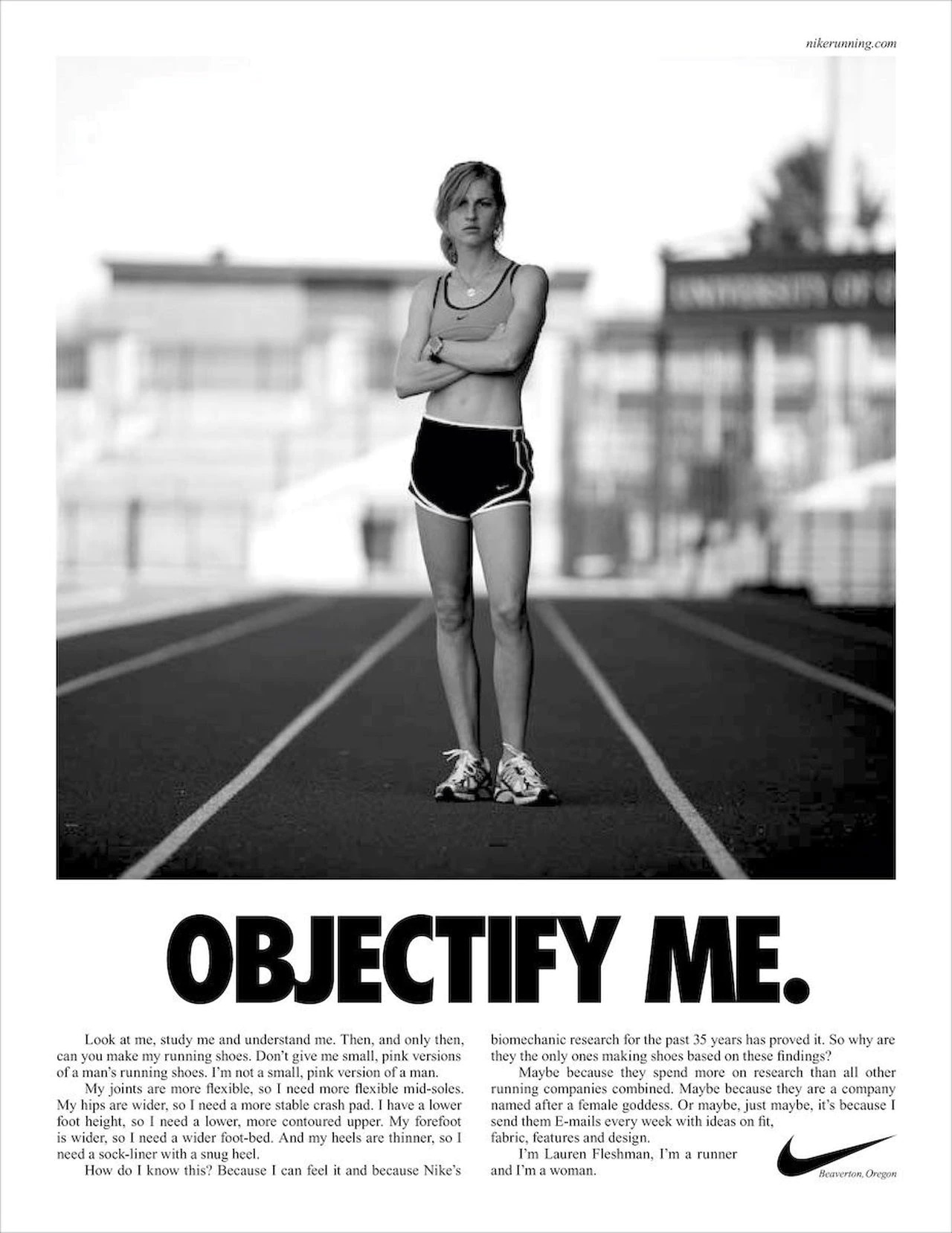

DE: I want to skip ahead in your life. I think it was 2007, you’re the reigning U.S. national champ in the 5,000; you have a six-figure contract with Nike; one day you’re looking through the Nike gear catalog, and you don’t see athletes; you see what you called “a sporty Victoria’s Secret catalog.” Around that time, Nike decides to put you in an ad campaign. But you weren’t thrilled with what they proposed. So you had the audacity to rewrite the ad copy and send it to them! Can you describe what happened and how it went over?

LF: The proposed image included a famous female athlete posing naked from a previous campaign. This was my big opportunity to be in an ad, so I didn’t want to be difficult. But I was wise to the fact that there is a trend in women’s sports media to sexualize them, feminize them, picture them in ways that are designed for the straight male gaze, almost as a form of assurance that we are still vulnerable, still seeking their approval. It made me sick to repeat this on a poster that would go on the walls of the next generation of girls, showing them that this is what “making it” looks like in sport. I decided, fuck that. You’ll have to read the book to find out how that went over haha.

DE: Haha, Ok. But I’m going to give readers a clue… 👇

DE: I think it was the following year, when one of the most dramatic scenes in the book occurs. With a lap-and-a-half to go at nationals in the 5,000, you moved out into lane 3, and stopped! After 13 seconds, you started again, in a sprint, and finished 4th, just off the world team. It’s kind of amazing that you stopped, and even more so that you started again so quickly. Why did you stop, and why did you start again?

LF: My internal chatter was so overwhelming, the pressure was so great, that I lost contact with the competitor I had been all my life. I convinced myself that it would be better to quit than to try my best and turn out the loser. I started again because I hated that voice and it didn’t match my values and I didn’t want to let it win.

DE: After that, you became the subject of some “headcase” gossip in the running world. But you grew from it. Pretty soon, you were actually having fun again. At a big race in London, which you won, you write: “I felt more free from perfectionism than I had in years. I took a drag on a stranger’s cigarette. I danced to a busker’s drums on the sidewalk.”

It’s interesting that your highs and lows were often in such close proximity. It reminded me of Alain de Botton writing about how, sometimes, it is at the moment of peak achievement that we should feel the most compassion for the achiever, because it is just at that moment when they are learning that their great triumph doesn’t fix the deepest problem they’re grappling with. When I read that, it resonated deeply with my experience with my first book, of it becoming a surprise bestseller. It was amazing, and yet… I wonder if that resonates with you at all. Did achievement deliver what you expected personally?

LF: This is basically what happened after my first USA championship in 2006, which was followed by the dramatic scene of dropping out and starting again. Winning didn’t make me enough, or make me beloved in some permanent way. That’s what I wanted. I wanted assurance I would be loved. But it was temporary. The love from success is always temporary. You have to find satisfaction with yourself on your average day.

Thanks to Lauren for answering questions at length. Her book is a fascinating look inside the winding path of a prodigy in a sport where — at least at the pro level — athletes are largely on their own. So check out Good for a Girl.

And if a friend sent this to you, you can support Range Widely with a free or paid subscription.

Another way to show support is to share this post.

Thanks so much for reading. Until next time…

David

Such an inspiring read and amazing athlete who's exemplified what

growing with grace and perspective is all about!

Hey David, thanks for this one. What an incredible interview! Fleshman is so amazingly thoughtful, candid, and insightful. I hadn't heard of her before, so I'm really grateful you helped me learn about her story. Since I teach and coach young boys and girls, I found this one to be especially relevant for my life.

Can I ask a weird question about interviewing? Let me know if this doesn't make sense: one thing I've noticed you do here is an example of what I've seen others do both in written and oral interviews (like a podcast). Lauren would repeatedly have amazingly long and rich answers, and my inclination would be to respond to or engage with that answer in some way that probably doesn't read very well on a newsletter ("Wow that was so reflective" or "I can't believe your dad did that" or "Thanks for sharing that really difficult memory). But you (and talented podcasters/interviewers like Derek Thompson I've seen) don't do that at all. Instead you cut through that verbal fluff and jump right to your next question. How are you able to transition that smoothly while still keep the conversation flowing normally? I imagine you have a list of questions, but I also can see that you're good enough at this to avoid the trap of just reciting them one after the next. Did that question make sense? Thanks again.