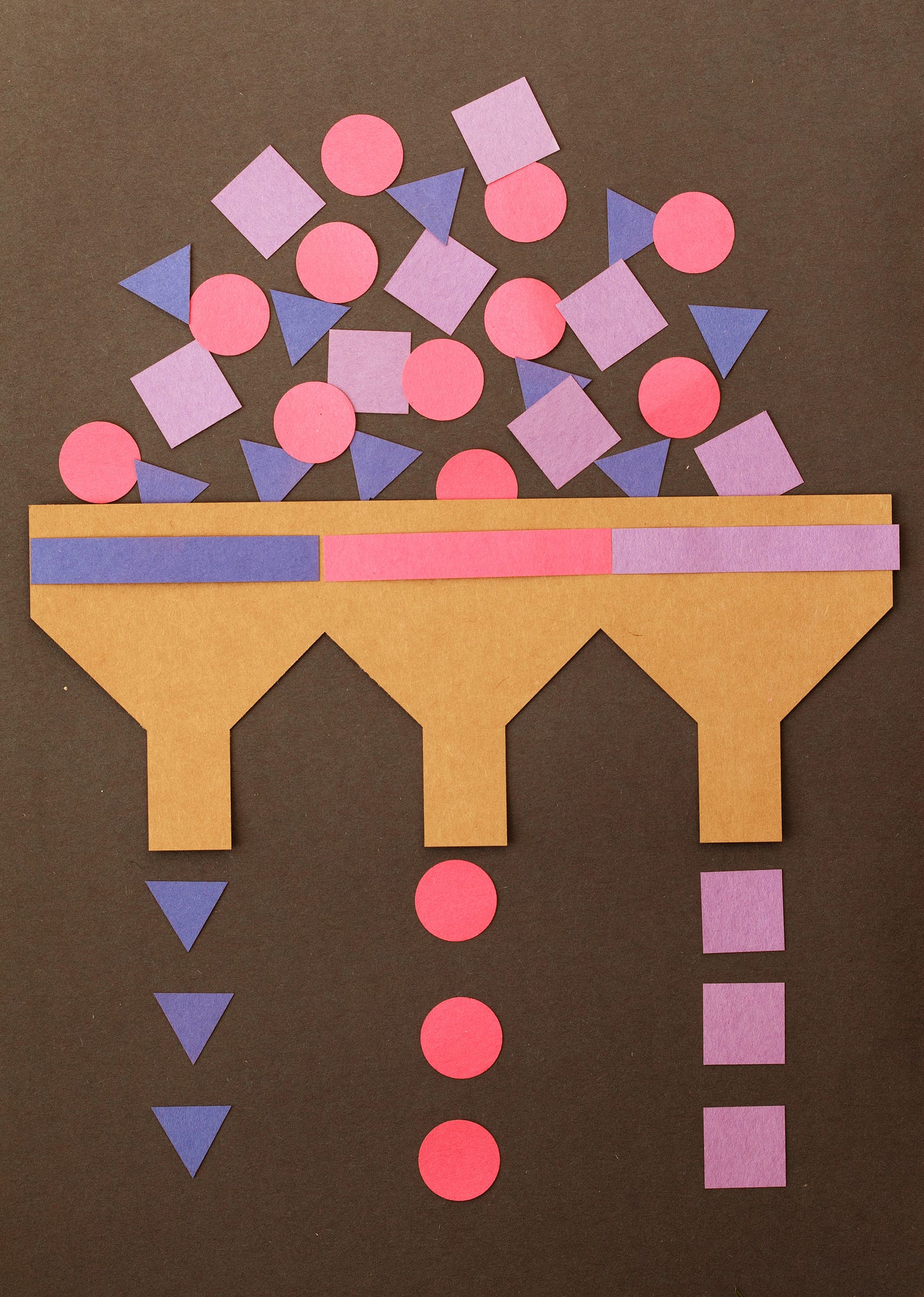

Keep The Talent Funnel Wide (Part 2)

Diversifying entry points makes room for "slow bakers"

I once joined a small meeting of coaches led by Chelsea Warr, who, at the time, was basically in charge of talent-development strategy for Olympic sports in Great Britain. Previously, she had been a physiologist at the Australian Institute of Sport.

She helped Australia and then Great Britain to stupendous performances when they respectively hosted the Olympics. At the meeting I attended, Warr discussed the need for talent-development pathways that accommodate both “fast risers” and “slow bakers.” My recollection of discussion among the coaches in the room was that they recognized that many of their top performers were “slow bakers,” who had developed slowly but steadily, or who found their niche relatively late.

That fast riser/slow baker dichotomy stuck in my head. I was thinking about it when I wrote my short “Keep the Talent Funnel Wide” post about youth sports in Norway. And I was thinking about it when I added a new story to Range in the afterword to the paperback edition.

That story is about Titus Kaphar, an incredible artist, MacArthur “genius” grant recipient (although he doesn’t approve of the genius designation), and avowed slow baker.

Kaphar (with fellow MacArthur grant recipient and poet Reginald Dwayne Betts) has a gorgeous (and large) book out, Redaction, based on an exhibit in New York City. Below is the book cover, and below that — with the permission of my publisher, Riverhead Books — I’ve reprinted Titus’s development story from the Range afterword. I hope you enjoy.

When asked, Titus Kaphar reflexively says that nobody in his family went to college. His mother didn’t go to college. His father went to prison, but not to college. Neither his grandmother nor his grandfather went to college. Nobody went to college. Except— he corrects himself — a distant cousin went to college. Kaphar himself certainly wasn’t going to college. He often didn’t even go to high school, hence the 0.65 GPA.

And yet, in his twenties, he decided to enroll in a few junior college classes. Allow him to explain: he wanted to date a soon-to-be teacher; she was four years older, contemplating grad school, and not impressed that he had no plans for his future.

“So I just went over to the junior college,” Kaphar told me, “kind of as a joke, not really taking it seriously, because, you know, I’m not an academic. I’m not a person who does really well in school.” He picked a few classes more or less at random. He came back and told the object of his affection. They had a quick laugh about it.

One class was art history. Why? “I probably read the word ‘art’ and thought, ‘Art should be easy,’” Kaphar told me. In an unexpected way, it was. Kaphar realized that he could remember details of paintings — not just remember what he had seen, but associate the painting with the style of a particular artist or artistic movement. “I remember one day we were talking about Van Gogh,” he recalled, “and I remember seeing the image and being very aware of where the painting sat in the history of art, where it sat in the timeline the professor was trying to lay out for us.” He began to contribute to class discussions. His confidence grew, and he got a B in the class.

“That was a new experience for me,” he said, “a B overall in the class at something that was academic. It made me go, ‘Hold up, wait a minute.’ I realized this was, in fact, something that I was enjoying, and I could feel myself wanting to push harder. When it became difficult, that grit became more apparent.” He took more classes, and tested strategies until he found something that worked, like dictating essays into a recorder for his first draft, and studying for history tests by focusing on connecting the images in a book to the surrounding material. Suddenly, college didn’t seem like such a crazy idea.

Kaphar proceeded to San Jose State University, to study fine arts. In an art history survey course, to his dismay, the professor skipped over the section on black painters. So Kaphar decided to compile his own syllabus on the topic. “I think to some degree, it was like being a reporter doing an investigation,” he said. A friend’s grandmother was a sculptor, and gave him books. The first was on the Harlem Renaissance. “That sort of opened the floodgates,” he recalled. He realized that the traditional artistic canon used in class was not some magical pantheon, but just another syllabus assembled by humans. He collected more books, and introduced new names into class discussion.

Eventually, he took an actual painting class, but the teacher told the class that he didn’t believe in painting anymore, so he gave no instruction whatsoever on technique. Instead, Kaphar started looking over other students’ shoulders and self-teaching. “It was like, last semester I painted an apple, and it looked like a cannonball,” he told me. “This semester that actually looks like an apple. Now, it’s loose, a child could do the same thing, but it looks like an apple. Awesome, let’s keep going.” He began to study paintings and then try to reverse engineer them. When he noticed that shadows in Velázquez paintings didn’t look flat, he experimented to find out why. It turned out he could get the effect by painting on a canvas that had a particular weave, and then scraping the paint back with a palette knife so that the weave itself broke up the brushstroke. “That right there is how I learned to paint, by looking a lot.” He spent hours in the studio, forgetting to eat because he was so engaged with the work. He considered himself extremely extroverted, but for the first time was finding fulfillment in an activity that he did quietly, in a corner, by himself. And he got better, a lot better.

He got so much better that a professor told him he should apply to the master of fine arts program at Yale. “What’s Yale?” he asked. The professor chuckled and showed him a pamphlet. Kaphar applied, and got rejected. The next year, he applied to Yale and a bunch of other grad schools. He got rejected from all of them. He resolved to apply to Yale every year. By that point, whether he got in or not was a secondary consideration. He had found his work identity. “I’m an artist,” he said. “I’m a maker, so I’m going to make.”

The resulting body of work eventually got him into Yale, where he was one of the oldest students in his class. Yale was not a place to learn technique, but by then he was used to self-teaching. At Yale he learned that some art critics had pronounced painting dead as an important medium. “I don’t understand how something that’s dead can make me feel so alive,” Kaphar said. So he kept making, churning out paintings, sculptures, and painting/sculpture combinations.

In 2011, Kaphar was researching his father’s prison history, and was surprised to find ninety-seven men with the same name who had been incarcerated. That spawned his “Jerome Project,” in which he used mugshots to paint portraits of the men on wood panels with gold leaf backgrounds (evocative of Byzantine portraits of St. Jerome) and with tar covering a portion of each face to represent a life scarred by prison. His work has now been featured in venues from the Museum of Modern Art and the National Portrait Gallery to the pages of Time magazine.

Today, Kaphar lives in New Haven, Connecticut, with his two kids and his wife—a.k.a. the older woman he wanted to impress by taking junior college classes. In 2015, Kaphar and a colleague founded NXTHVN (pronounced “Next Haven”), an art space created in a former manufacturing plant and where early-career artists can apply for a stipend and studio space. Those artists in turn mentor local high school students who are paid to serve as their studio assistants. For most of the high school students, it is their first job of any kind. Kaphar wants to diversify the entry points into the art pipeline, because imagine who we miss if we force every Titus Kaphar to find his vocation by chance alone.

In 2018, Kaphar won a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, colloquially known as a “genius grant.” He doesn’t love that moniker, however. He doesn’t really like the word “genius” at all. It makes it seem as if someone was plopped on Earth magically knowing what to do and how to do it. It doesn’t seem like it could encompass someone who took a junior college class hoping for a date, and accidentally found his path.

“In that class,” Kaphar told me, “I realized that I had a visual intelligence that no one had ever asked me to use.”

Thanks so much for reading. This story embodies a number of concepts that come up repeatedly in Range — from the notion that “we learn who we are in practice, not in theory,” to the idea that “when you get fit, it looks like grit” — and it was a perk of my job to pepper Titus with questions. (If you’d like to read the story in context, it’s only in the afterword added for the paperback, but every ebook should automatically update with it.)

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

If a friend sent this to you, you can subscribe here:

Until next time…

David

[cover image by Igor Kisselev/www.close-up.biz via Getty Images]

Another great post! But in some ways its depressing. To think of all the potential out there, that will never be known because of the way our educational systems work. Because of the way our society functions. It truly was happenstance-- a bringing together of several different people/activities all at the same time that led Kaphar to become who he was and do what he did. If just one of those elements was missing-- would you have been able to tell the story you did? I guess in some ways, we can’t control for this, other than trying to get folks to appreciate that everyone has different skills, abilities, methods of learning, and that we all provide value, and ought to be allowed and given the opportunity to figure out what that is. What would society be like if we did that?

I loved this story and related to it in a lot of ways. Self-learning is what gets most of us through art school, not that there weren't some amazing professors, but some of those open-ended exploratory classes, were a bit of a nightmare. Something about having time to sit and stew in your own curiosity can create amazing results if you learn to teach yourself.