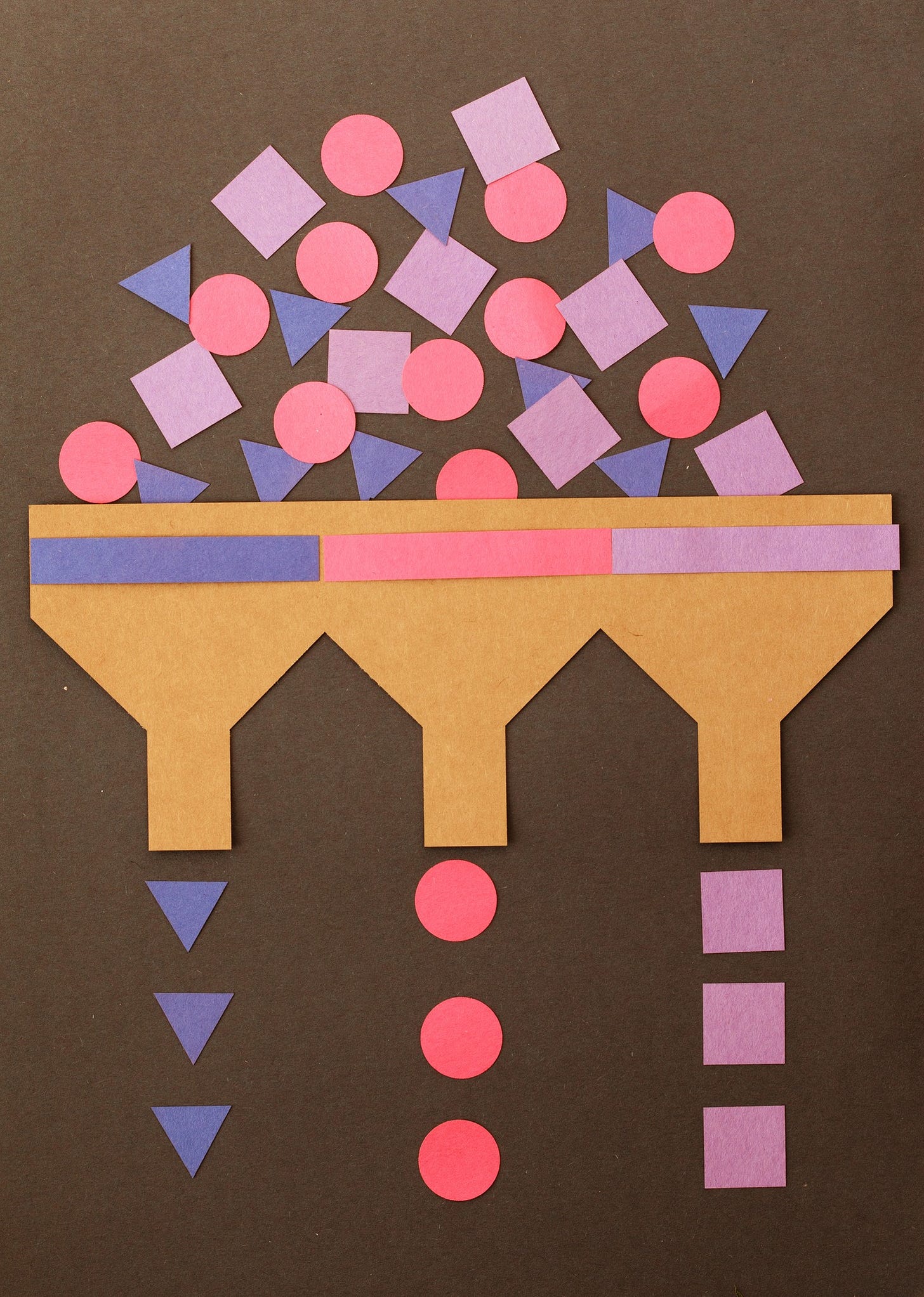

Keep The Talent Funnel Wide

Pushing talent selection earlier than necessary is a great way to ensure worse results

Welcome to Range Widely, where I hope to help you think a new thought in a few minutes each week. You can subscribe.

If you’re new to RW, here are two of the most popular posts: “Tik-Tok Tourette’s”, and “A Technique Championed by Russian Writers (And Fraggles) Can Give You a New Perspective.”

Norway is home to 5.4 million people — smaller than metropolitan Atlanta. At the 2018 Winter Olympics, Norway won 39 medals, which was equivalent to the total for the United States, China, Great Britain, and New Zealand (pop. 5 million), combined. They also did quite well in the last Summer Games; they won gold in beach volleyball, which you might not reflexively associate with Norway.

This Winter Games, the Norwegians were a real let-down. They only won 37 medals, 5 more than second-place Russia, and 10 more than the U.S. So: what’s going on with Norway? Well, a lot of things. Performance is multifactorial. But I want to share one thing that isn’t going on in Norway, and that’s youth sports that mainly serve adult economic interests.

HBO RealSports did a great segment on youth sports in Norway. Participation and fun are the priorities. Costs are low, and optional. And there is — get this — a national prohibition against keeping score or ranking kids before age 12.

Check out the short clip below.

This is by no means to say that Norway is a sports utopia. (By virtue of having written about misuse of prescription drugs in sports, in 2016 I was on a panel in Norway about that very issue among Norwegian cross-country skiers.) But there’s a lot to learn from their development programs.

The last place I lived in New York City was near the meeting spot for a travel soccer team for seven-year-olds. I’m still waiting to meet the person who honestly thinks that seven-year-olds have to travel because they can’t find good enough competition in a city of 8 million people. They probably spent more time traveling than playing.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the last decade talking with sports scientist Ross Tucker about the principles of good talent development pipelines. And one practice we’ve often come back to: not forcing selection earlier than necessary. People develop at different speeds, so keep the participation funnel wide, with as many access points as possible, for as long as possible. I think that’s a pretty good principle in general, not just for sports.

Thank you for reading. If you found this post valuable, please forward it to a friend, or share it with the button below.

As always, you can subscribe.

Until next week…

David

P.S. I recently joined Instagram. And then, inspired by Daniel Pink’s The Power of Regret, (specifically the part about how regrets of inaction linger much longer than regrets of action), I recklessly posted a video that I found a little embarrassing. But the feedback was fun, and hence I will do it again. So follow me there if you want to see some inchoate dance moves.

P.P.S. If you’re interested in youth sports, I recommend The Reformed Sports Project Podcast. I was just on it recently, and you can listen to that here. Or, better yet, listen to the episodes with luminaries like Bob Bowman (coach to Michael Phelps and at Arizona State University) and Anson Dorrance, coach of UNC women’s soccer, probably the greatest dynasty in college sports. UNC has won 21 of the 40 NCAA championships ever contested! The lessons in those interviews often go beyond sports.

[cover image by Igor Kisselev/www.close-up.biz via Getty Images]

When I lived in Germany and learned about the 'education pipeline' that kids were subjected to there, I was completely shocked. The way it was described to me is 100% at odds with what you suggest here is the way to go. What I heard was that by around age 10, kids would be funneled into different types of schools, basically on an academic track or a vocational track, based on their grades and perceived intelligence and capability at age 10. I'm not sure if things have changed since my time there, but I remain completely in shock that this would ever have been a practice.

When I expressed shock and disbelief, I was told, "You might not like it, but this is why our economy is so good."