I’m going out on a limb with a bold election-season prediction: there’s going to be a lot of conflict. At the national level, obviously, but also at the level of colleagues, friends, and family.

A few years ago, I was fascinated by the book High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out, by journalist Amanda Ripley, whose work I’ve long admired. Ripley’s reporting on conflict management spanned astronauts who were stuck together to gang members who wanted to break apart.

In addition to being a journalist, Amanda is a trained conflict mediator and the cofounder of Good Conflict, which trains people to navigate conflict in a productive manner. She has even worked with members of Congress and their staffers, on both sides of the aisle.

In this season of dispute, I invited Amanda to talk strategies for turning high conflict into productive conflict. Our conversation is below.

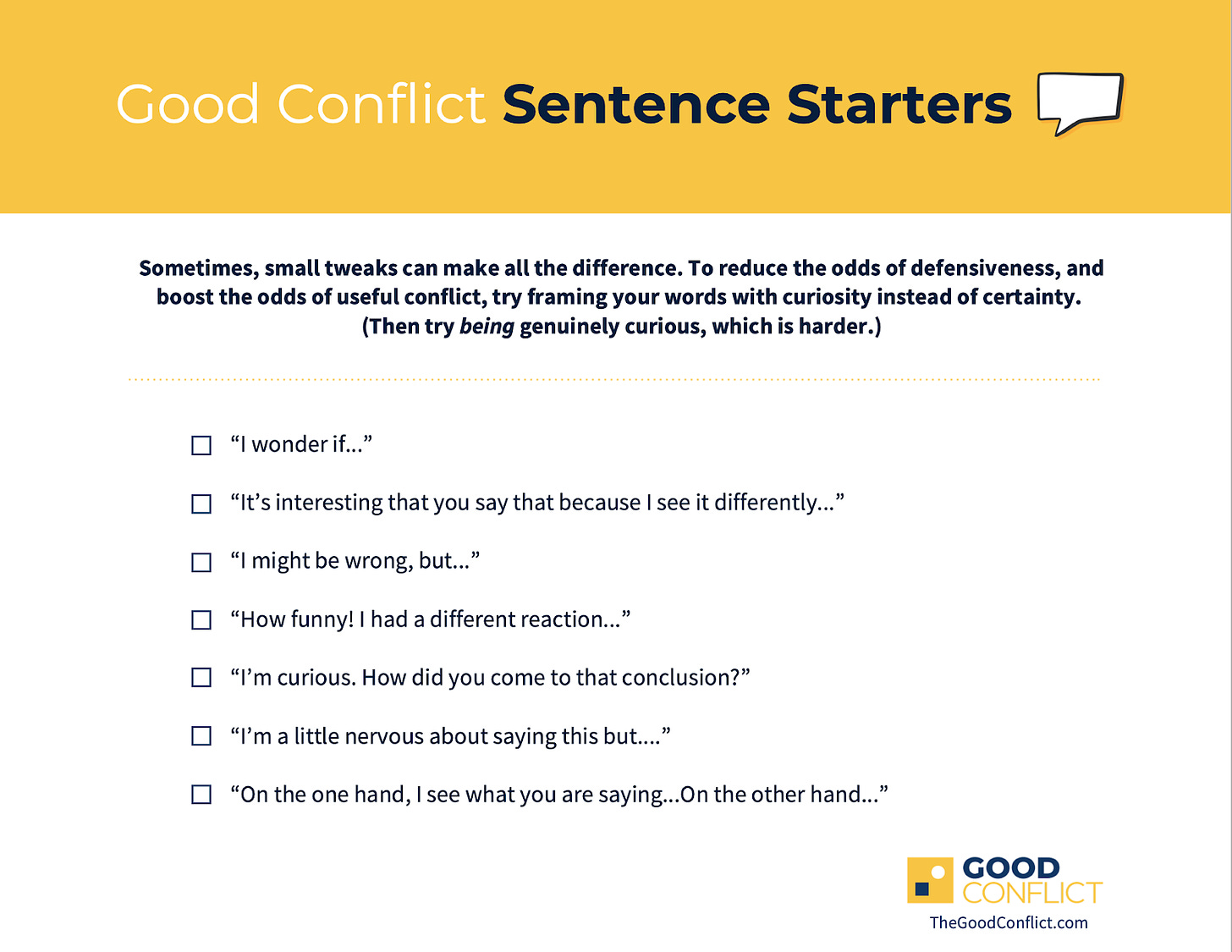

David Epstein: You’ve pointed out that small conversational tweaks can make a big difference in preventing a discussion from spiraling into defensiveness. It makes me think of when someone says, “With all due respect…” Because when I hear that, I kind of assume they mean the opposite, and that triggers some defensiveness. So what’s a better way to lead into disagreement?

Amanda Ripley: Part of what we want to do is shift from being judge, or jury, or victim, or villain in a conversation to becoming more like a detective. And that can be a really hard turn to make. So it helps to have some actual sentence starters that you can practice in advance in low-level situations, to make this automatic.

DE: You and your Good Conflict cofounder, Hélène Biandudi Hofer, just started sharing some free resources for navigating conflict. And the “sentence starters” tip sheet caught my eye.

AR: I actually just used one the other night. I went to a dinner, and I was there for about two minutes before someone, an academic, said something to me about the media that I just profoundly disagree with. I literally said: “Oh, wow! That's so interesting, because I feel the exact opposite way.” And if you can say it in that tone of genuine delight and curiosity, while acknowledging straight-up that you totally disagree, it's like this portal opens up. You've reframed disagreement to be something really intriguing and compelling and safe. It’s almost the same tone you would use to say: “Oh my God, I went to that same high school!”

DE: You mentioned practicing this in low-level situations. I’m a huge fan of low-stakes practice in all things. I’m naturally a bit shy, which would probably surprise even some people who know me well. And when I was moving out of science grad school — which didn’t involve much interaction with strangers — to journalism, which did, I learned very quickly that approaching strangers didn’t come naturally to me. So I started forcing myself to strike up conversations in elevators. It’s very low-stakes practice. As long as the person isn’t getting off on the same floor, it’s completely over in thirty seconds, and you can lick your awkwardness-wounds very quickly. And it was almost never as awkward as I feared it would be. In any case, low-stakes practice was really helpful, and now I don’t have a problem with it.

AR: That’s actually quite challenging for most people, especially if you feel a little bit shy. But that’s basically exposure therapy, right? It’s a mini dose of exposure.

DE: I suppose it is. At the same time, I wasn’t starting arguments with people in elevators, so I’m wondering if you have suggestions for low-stakes practice when it comes to conflict.

AR: There’s a paradox with conflict: if you want to get better at it, you have to have more of it. But there’s a huge spectrum of how threatening different situations feel to us. I think practicing is actually easier than it sounds, because we’re always encountering people who we don't understand, even if we aren’t having an actual conflict. Let's say you're in line at the supermarket and the person in front of you is getting, I don't know, seventeen papayas, and you have some questions in your head about why that would be and what that means about them. If you’re using Dave's elevator approach, you find a way to be like: “Oh, wow! That's a lot of papaya.” Just really lean into it with curiosity. That's not a conflict, but that's a beginner level of saying: I'm going to get very curious about you in a way that's non-threatening. You could even say: “I don't know what it is, but I've never liked papaya. I feel bad about saying that to you, because you obviously love papaya.” …Dax Shepard does this very well on his “Armchair Expert” podcast. He’ll say: “Really?! That's so interesting! Because I feel like it's the exact opposite.” And you can hear the delight in his voice, and it’s hard to articulate how much it changes the energy, even as a listener, because it’s so different from what we’re used to.

DE: I find that especially interesting to think about in terms of interviewing, because when I’m being a journalist, I’m almost unprovokable. I’m totally provokable in my private life, but when I’m reporting, everything is just a curiosity. The more challenging the claim that somebody makes, the more interested I am to learn more about it. It reminds me of something I learned back at Sports Illustrated, when I worked on investigative stories with Selena Roberts, who was much more experienced. She would often say things to people she was interviewing like: “I’m trying to understand…” or “Can you help me understand…” I think it was her way of saying: “I’m trying to see this from your vantage point but I’m having trouble doing it, and I need your help.” And, in fact, it often led those people to explain their views in detail, and it was a way of openly sharing things we were confused about without being combative.

AR: So much of conflict is: How can we get on the same side of the table here? So that, even as we disagree, it's not purely adversarial.

DE: While we’re talking conversation techniques, I want to ask you about one that I learned from your work, and that I know is hugely important: “looping.” Can you explain what that is?

AR: “Looping for understanding” is a technique that Hélène and I learned from the Center for Understanding in Conflict, which is one of the places where we trained. And there are a million active-listening techniques out there, but we like this one because it uses words to show not just that I'm trying to understand you, but that I know I'm probably not getting it right.

The steps are: listen to what's most important to the other person — not most interesting to you, but what seems most important to them — then distill it into your own most elegant language, and then play it back. And then — and this is the one that's easy to forget — check if you got it right. It's almost like what you mentioned with Selena, when she was saying: Help me understand this. For example: “It sounds like you're saying that this election makes you feel profound despair, and most of all you wish it were over and you could just come back in a month. Is that right?” And just doing that all of the sudden reorders the universe, because people can sense that you're trying. And then they start to correct you, or add on. They also get to hear themselves, which is really, really important.

Chris Voss, the hostage negotiator, has written about this. Basically, you're trying to get them to hear what they're saying, to see if it makes sense to them. Particularly with emotional people, it's very hard for them to articulate what they mean, and they don't even know some of the time. So it has this whole galaxy of effects on the conversation, and usually people lower their guard and say more about what they really mean. They might add on, or they might say, “exactly,” which is when you know you've gotten it.

DE: And so, were you saying that you really want to focus in not just on the thing that most interests you, but the thing that seems most important to them, and then summarize that, and then check is that correct?

AR: Yeah, exactly. Because, Dave, when you're doing that —

DE: Did I just do it?

AR: Ha, yes! Yes, you did it. That was great. And you made me realize something else, so I'm going to add on, which is: if I'm listening to what's most important to you, I'm more in your journalist mindset. If I can get into that detective or scientist or journalist mindset, then I'm less provoked. And one way to do that is to look for cues to what is most important to this person. Then it's less about me, and how I feel, and my advice and my opinion. So what you're listening for in order to figure out what's important to them are words that are a little stronger than maybe you expected. Metaphors are also a good sign that there's something important there. Usually, when people use an analogy, there's something deeper there, and they want to tell you more.

DE: Yeah I guess I use analogies when I really want something to stick, so that makes sense…By the way, looping also reminds me of advice from Harvey Karp, the pediatrician who wrote The Happiest Baby on the Block. In his book on parenting toddlers, he has what he calls the “fast food rule”: when your toddler is freaking out, you repeat back to them what they just said. “So you’re really mad that you didn’t get such-and-such, and what you want instead is this other thing, right?” And maybe you can’t fix the problem, but at least you’re saying I understand that you feel hurt, and you’ve been heard. And it’s called the “fast food rule” because it’s similar to a drive-through where you order two burgers, fries, and a drink, and the person says back to you: “So that’s two burgers, fries, and a drink, right?” Yes, we’re good to move on.

AR: Have you tried that with your own son?

DE: Some. I mean, we have this nightly thing that developed organically that we just call “feedback.” We both give positive and critical feedback to one another about things that have happened. And when I get critical feedback, I definitely try to summarize it back to make sure I’m understanding it in adult language. It’s actually a pretty fun ritual, and probably 80% of it is just us telling one another what went well.

AR: That’s how you develop comfort with this stuff. So when he’s 15, you can say: Remember that thing we used to do? …Some people disagree with me on this, but I found that the best way to practice looping, hands down, is in parenting. I’ve been told that sometimes with a toddler it doesn’t matter what you say; by the time I learned looping my kid was 10, and I found it to be this third door that I didn’t know existed. I don’t have to argue; I don’t have to threaten; I don’t have to surrender, but I can make you feel heard, genuinely, which is half of what people want. And then we can move on.

DE: Yeah I don’t think there’s always a perfect solution for toddlers, because if someone’s demanding toast without bread, I feel that’s a conflict where there’s just no real solution, and you have to wait for it to pass.

AR: Right. No amount of saying: “You really wish you could have toast without bread is that right?!” None of that is going to work.

DE: Correct me if I’m wrong here, but of all the strategies you talk and write and coach about, I feel like looping has a special importance.

AR: Yes, because there’s so much underneath it. There’s so much about humility and trust building. We’re living in an age where we all have microphones and a broadcast antenna in our pockets, and yet we almost never feel heard and understood. So when you're living in a time where people do not feel significant, or like they're part of something, then helping each other feel heard and really trying to understand each other is a superpower. This is what Charles [Duhigg] wrote about in his last book [Supercommunicators]. It's an incredibly powerful thing. We like looping because: it’s easy to teach; most people are terrible at it — including, I would say, Congressional staff…most people need to get better at it, and they can get better very quickly. It’s by far the most popular thing we teach [at Good Conflict]. There’s nothing else that has changed my behavior more radically on a day-to-day basis than looping in the past twenty years.

DE: I want to ask you about another term that you’ve used, and I’m not sure if you actually coined it, but I think it crystallizes something important: “conflict entrepreneurs.” These are people who are profiting in some way from stoking conflict, whether that’s financially, or in terms of attention, or something else. And I think we've all experienced that on social media, but one of the Good Conflict videos that you made talks about this in real life, with conflict entrepreneurs at work. Can you describe a conflict entrepreneur — not on social media, but that might actually be someone in your office or your inbox?

AR: I did not coin the term. It usually was used internationally in hot conflicts. So, war zones, and it meant literal war profiteers — people who are selling weapons. The only thing I added to it was to apply that to people who are doing everyday kinds of conflict entrepreneurship, which is particularly relevant now because we've created entire institutions that celebrate and reward conflict entrepreneurship, including social media. We're living in a golden age of conflict entrepreneurs, and it’s really helpful to have that vocabulary, because once you see it, it's hard to unsee.

Now, to answer the question of: How do we know it when it's up close and personal in our everyday life? In politics and social media, it's fairly obvious. With pundits, you can tell when someone has a whole brand built on that. With regular people in our everyday life, what I've learned is that you have to come at it with a little more compassion and realize that usually people who have a history of getting stuck in cycles of blame and grievance and hostility, usually they’re dealing with some kind of internal trouble that they haven't been willing or able to deal with. And that's also true, by the way, for professional conflict entrepreneurs in Congress. They are spreading their pain around in a way that seems to work for them on some level, to give them a sense of purpose, a sense of belonging, a sense of significance. It is a kind of power to stir the pot. And this doesn't mean someone who goes to HR with a complaint, or who wants to unionize. We’re talking here about people who repeatedly see conflict where there isn't any, and particularly seeing disrespect and harm where there isn't any. It usually reflects somebody who needs some help, and probably, if they got that help, wouldn't be doing this.

DE: And so what do you do if you’re in a situation where you have to work with someone like this? I know there’s no perfect answer, but do you have suggestions for what to try?

AR: When I wrote High Conflict, everyone who shifted out of high conflict into good conflict, they all distanced themselves from the conflict entrepreneurs in their lives in different ways. Curtis Toler, who was a gang leader, literally moved across town to a different part of Chicago. A novice politician got a different advisor. And when I wrote the book, I thought: Here’s the answer; you’re welcome world. And then a bunch of people came to me after reading the book, and said: Okay, great. What about when you can't do that? When you can't distance yourself from conflict entrepreneurs because they are your boss or your colleague or your father-in-law or your president? What then? And so I went off and did the one thing I know how to do, which is go out and talk to other, wiser people, and I wrote a piece for Harvard Business Review, about managing conflict entrepreneurs. I learned a lot from Gary Friedman [who started the Center for Understanding in Conflict], and he said: if they're 80% conflict entrepreneur, see if you can talk to the other 20%. With some people, you can figure out what else matters to them, what other identities they have. Often, it's as a parent, or it could be as a neighbor, or an American, or a veteran — whatever; find out more about them. This is counterintuitive. It's literally the opposite of distancing yourself. Find out more about them and see if you can speak to the 20% and channel a little bit of that energy into a shared problem.

There’s also a business-friendly acronym that a place called the High Conflict Institute has developed: BIFF, and this is how you respond to a conflict entrepreneur over email or text or slack when they come to you with something. It’s: “brief, informative, friendly, and firm.” It doesn’t make them not a conflict entrepreneur, but you’re trying to contain them, and not take the bait. Give them just a little bit of what they need, a little bit of validation.

DE: I had a friend recently who was in a sort of spiraling conflict with someone at work, and this wasn’t a conflict entrepreneur situation, but she asked the person for help with something they were both unhappy about. And it seemed to work. Actually, I’ve heard almost this same exact thing from two friends fairly recently. In the process, it turned out that the person was really upset about some other thing that had nothing to do with the apparent source of conflict at work. And I think this gets at what you call the “understory,” so can you explain what that is?

AR: Every conflict has the thing that we fight about and then the thing it's really about underneath. And that’s usually one of four things. It's almost always: respect and recognition; power and control; care and concern; or just flat out stress and overwhelm. But the faster you can identify what the understory is for you and for the other person, the more useful that conflict can be. Your friend had a really great idea, which is to get out of that adversarial position, get on the same side of the field, and try to solve the problem together. And I hadn't really thought about how, in doing that, you might get to the understory. Typically, in our workshops, we train people to use looping and different questions to get to the understory. But actually, from all the research on social identity theory and human behavior and conflict, working on a shared problem makes a lot of sense as a way to create enough alliance that people will reveal more about what's really going on.

DE: Otherwise you probably have very little chance of getting out of a conflict if you don’t know what it’s really about, right?

AR: This is what we see right now. It's like there's infinite fuel for more and more conflicts in our country, in our public life. There's always going to be something, unless and until you can identify the understory. Actually, there are a lot of fights we need to have in this country, but we keep having nonsense fights about the wrong thing at the wrong time, and so trying to figure out what is that right fight requires that investigative, detective mindset.

DE: One thing that convinces me that we're having nonsense fights is how little hypocrisy matters. Everyone will call out hypocrisy on all sides of political debates all day long, but it has no currency because people aren't actually fighting about the facts that someone is being hypocritical about. So it just has no currency whatsoever.

AR: That's a good point. It’s not really about that thing. It’s almost like arguing with a toddler sometimes, right? It doesn't really matter what the thing seems to be about, but we keep repeating that we want toast with no bread, over and over and over.

DE: And it’s not that I don’t want toast without bread, because I do, it’s just that there’s other stuff going on underneath.

AR: I mean, that would be amazing…No carbs!

Thanks to Amanda for her time, and thank you for reading. And if you enjoyed this newsletter, please share it.

If a friend forwarded this to you, you can subscribe here:

Until next time…

David

This was a great article. I am now a heart transplant patient mentor, and these ideas and strategies will be very helpful for me in discussions that I have been involved in.

A big thank you.

Apparently Rogers influence is wider than I thought

https://www.listeningway.com/