A Spartan king, asked what the Spartans gain from their ‘spartan’ habits, replied:

“Freedom is what we reap from this way of life.”

I underlined this anecdote in Ryan Holiday’s book, Discipline is Destiny, which came out last year. I think it’s a microcosm of the book as a whole, which argues, in my view, that self-imposed limits — of body and mind — can free rather than restrict us.

Ryan’s book has been on my mind a lot lately, while I’ve been reading about — and in some cases visiting — writers I admire. A commonality that jumps out is the degree to which these (usually self-employed) people proactively structure their lives so that they can be as free as possible in their creative time.

Haruki Murakami, one of my favorite writers, has compared writing to endurance sports, and in fact went from living a pretty unhealthy, nocturnal lifestyle back when he was running a jazz club, to using endurance training as part of his writing process. Here’s how he described it to the Paris Review:

When I’m in writing mode for a novel, I get up at four a.m. and work for five to six hours. In the afternoon, I run for ten kilometers or swim for fifteen hundred meters (or do both), then I read a bit and listen to some music. I go to bed at nine p.m. I keep to this routine every day without variation. The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind. But to hold to such repetition for so long—six months to a year—requires a good amount of mental and physical strength. In that sense, writing a long novel is like survival training. Physical strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity.

Maya Angelou would rent a hotel room for her writing, and have all the artwork removed from the walls to avoid distraction.

All of the systems and habits I’ve encountered are a little different, but in general they are thoughtfully contrived. As Ryan writes in his book, Toni Morrison would tell her students:

“One of the most important things they need to know is when they are their best, creatively. They need to ask themselves, What does the ideal room look like? Is there music? Is there silence? Is there chaos outside or is there serenity outside? What do I need in order to release my imagination?”

If you know Ryan’s work, then you probably know that he has written voluminously about Stoic philosophy, and its applications to modern life. In Discipline is Destiny, he likened Morrison’s advice to the Stoic notion of kosmiotes, or orderliness. “Chefs speak of mise en place,” he continued, “prepping and organizing everything you need before getting down to work.”

I’ve enjoyed a number of Ryan’s books, but this one in particular came at the right time, just as I was realizing that I needed to add more structure to my workspace, and to my workday. In this era of hybrid and remote work, I expect many of us could benefit from putting more thought into self-imposed structures.

Below is a short Q&A with Ryan, in a form I’ve never tried before. I chose four images that came to mind while reading Discipline is Destiny, and structured the Q&A around those.

Like much of Ryan’s work, the book is packed with fascinating historical nuggets. If you pick it up, consider ordering from The Painted Porch, the independent bookstore Ryan runs in Bastrop, Texas. Without further ado…

David Epstein: There’s so much in this book that got my brain gears turning that it’s hard even to know where to start. But let’s zoom in on a few people you featured who — while well-known — aren’t usually prominent in books about personal development.

Image one: my fellow Columbia alum Lou Gehrig, a.k.a. “The Iron Horse.” He starred in both football and baseball, and supposedly hit dingers through some windows in the music building on campus.

But the lore was that he didn’t like the place because his mom worked as a cleaner in one of the rich-kid frat houses. But, whether it was that frustration or some other, you note that he seemed to channel every slight into discipline. Never missing class; giving up drinking; and not because he was a square, but because — and I love how simply and powerfully you put this: “It meant something to him to be a ballplayer, to be a Yankee, to be a first-generation American, to be someone who kids looked up to.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of giving ourselves clear, useful constraints to direct our lives. And it sounds like he had a strong set of values for his work, and that made the resulting discipline, if not easy, at least obvious. It reminds me of “flow” psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who wrote that when you choose to invest in a marriage, you preclude a lot of freedoms and yet can become liberated, because — if you’re truly invested — you can start spending time living instead of wondering how you should live. Or perhaps a bit like what Cicero once wrote: “We are servants of the law so that we can be free." You choose limits in order to allow freedom, in a sense.

From my vantage point, you’re incredibly disciplined, and it feels to me like you’re helped in that by a clear network of values, or a clear portfolio of things in which you invest energy that simultaneously constrain and liberate. So I was wondering if you could fill in the Gehrig phrase for yourself — “It meant something to Ryan to be…”

Ryan Holiday: Oh, it means something to me to be a writer — to be an author. I think that’s just the absolutely highest privilege there is. I think you and I have talked about this before, I really get upset when I talk to authors who don’t write or don’t publish and I really can’t stand people who see books as a means to an end (that is, speaking income or consulting income or influence or a campaign tool). Western Civilization is built on the backs of these great texts and while I am not saying that I or anyone I know is creating anything close to that, I feel like we should at least try. We should try to make great stuff and be great at what we do.

So for me, this window I have where publishers want stuff from me, where I have an audience, where I have the energy — while I am literally alive — I intend to make the most of.

DE: The next image I want to discuss is of Angela Merkel. She’s one of the leaders you write about as a model of simultaneous restraint and dedication. You reminded me of a fascinating political moment in 2007, when Merkel was meeting with Vladimir Putin in Sochi. He knew she was afraid of dogs, so he made sure to let his very large black labrador off the leash and into the room so it would sniff around Merkel. You can see below, Putin is smirking, and Merkel is clearly uncomfortable, but — as ever — keeps her composure.

Perhaps that’s why Putin was supposedly more unnerved by her than any other leader. I’ve read that Putin’s buildup of the Ukraine invasion coincided with the winding down of Merkel’s tenure — not coincidentally. He couldn’t rile her. (I should note, she’s currently receiving criticism for having intertwined the German and Russian economies.) She remained totally cordial during the meeting. Then later, she commented:

"I understand why he has to do this — to prove he's a man. He's afraid of his own weakness. Russia has nothing, no successful politics or economy. All they have is this."

Putin is engaging in very loud theatrics here. But as you wrote, Merkel also knew that politics is a “show,” as she said. The show she puts on, even down to her clothing choice, is just different. I thought this part of Discipline is Destiny was unusual and so interesting. How would you describe her “show”?

RH: Merkel is very interesting in that she both refuses to play the politics as showbiz game…while astutely playing it. It’s sort of an ‘obstacle is the way’ move — you know she is not young or stunningly beautiful, she’s not necessarily charismatic. But she’s not a slob. She’s not intentionally boring. She perfected this kind of middle ground there that proved to be quite compelling. She comes off as a confident, intellectual, reasonable lady. She had this great line, “You can’t solve tasks with charisma,” which is itself kind of a jujitsu move. It’s funny. It emasculates her more telegenic opponents, kind of one-ups her over other world leaders. It implies that she actually can do the tasks or the job — which she then largely proved.

The reason I wanted to include her in the book — she’s also a character I studied in Ego is the Enemy — is that I wanted to show there are many different forms of discipline. It’s not just the stamina of Lou Gehrig that we should be impressed with. There was famously a paperweight on her desk while she was in office that said basically, “There is strength in calmness.” This is a very underrated trait in leaders. Less famously, one of Washington’s favorite sayings (coming from a play about Cato) was to look at things “in the calm light of mild philosophy.” Again, we need more of that.

DE: In the “Avoid the Superfluous” chapter, you write that Michelangelo “avoided the gifts dangled by his wealthy patrons. He didn’t want to owe anyone. Real wealth, he understood, was autonomy.” This reminded me of one of my favorite paintings: Rembrandt’s Aristotle With a Bust of Homer. The meaning is ambiguous, but you can see below — in image #3 — that Aristotle’s right hand is elevated, in the lone beam of light, atop the bust of Homer. His left hand, lower and in the shadow, is touching a gold pendant, presumably depicting his student, Alexander the Great. The gold chain is an honor bestowed by Alexander.

You write about Alexander’s unbridled ambition, and I can’t help but feel that, in this painting, the honor is more like a fetter. The hand in the light is contemplating knowledge, and perhaps Aristotle’s past and the past of Greece, while the hand in the shadow grasps the present — a literal gold chain gifted by a wealthy patron who wanted to conquer the entire world. The chain seems sad to me, rather than triumphant. You’re so well read in Greek history, I’m just curious if you have a different interpretation to share, or anything to add about a painting I love.

RH: The Roman poet Juvenal had a line about Alexander. It’s something like, “In life, the world was not big enough for Alexander’s ambition. In death, a coffin was sufficient.” We look at these characters all these decades or centuries later–Alexander, Caesar, Napoleon — as sort of role models. Of course, in reality they were deranged and awful. Generations were destroyed, pointlessly in most cases, for them to work out their mommy issues. In Meditations, Marcus Aurelius points out that, you know, in the end, Alexander and his mule driver both went into the same ground. Who cares?

And yeah, it’s also an under-discussed point that these maniacs also suck in and corrupt other smart, talented people. Da Vinci wasted years of his life chasing the favor of Cesare Borgia. Aristotle followed Alexander around. Nero sucked in and ultimately killed Seneca. I get how it happens, I mean, in my own life I worked too long for people I should have walked away from. Salary is an intoxicatingly stable thing when you’re an artist or an intellectual, I think. You think it will be the platform from which you can do your best work — that it’s the security you need or deserve. You also like the influence or relevance it gives you. But in the end, it is a trap.

DE: On to our final image. You write a lot about “keeping the main thing the main thing,” as Stephen Covey put it, and carving out large blocks of uninterrupted work time for whatever that is. This really resonated. While working on both of my books, I did a pretty good job of keeping the main thing the main thing. I had a joke that my Game of Thrones-esque house words were: “When My Book Is Done,” because it was my answer to every question.

Then the pandemic hits. I went into it with a one-year-old, and the travel I was doing in the aftermath of Range stopped overnight. My head was spinning and I lost track of the main thing, professionally speaking. I started doing a lot of low-value stuff just to get something done. I was extremely busy, yet accomplishing very little. When I’m really in researching-and-writing mode, any unit of measure less than, say, half a day, is basically useless for getting something really meaningful done. I only recently started to get back on track, which means having to say “no” a lot more.

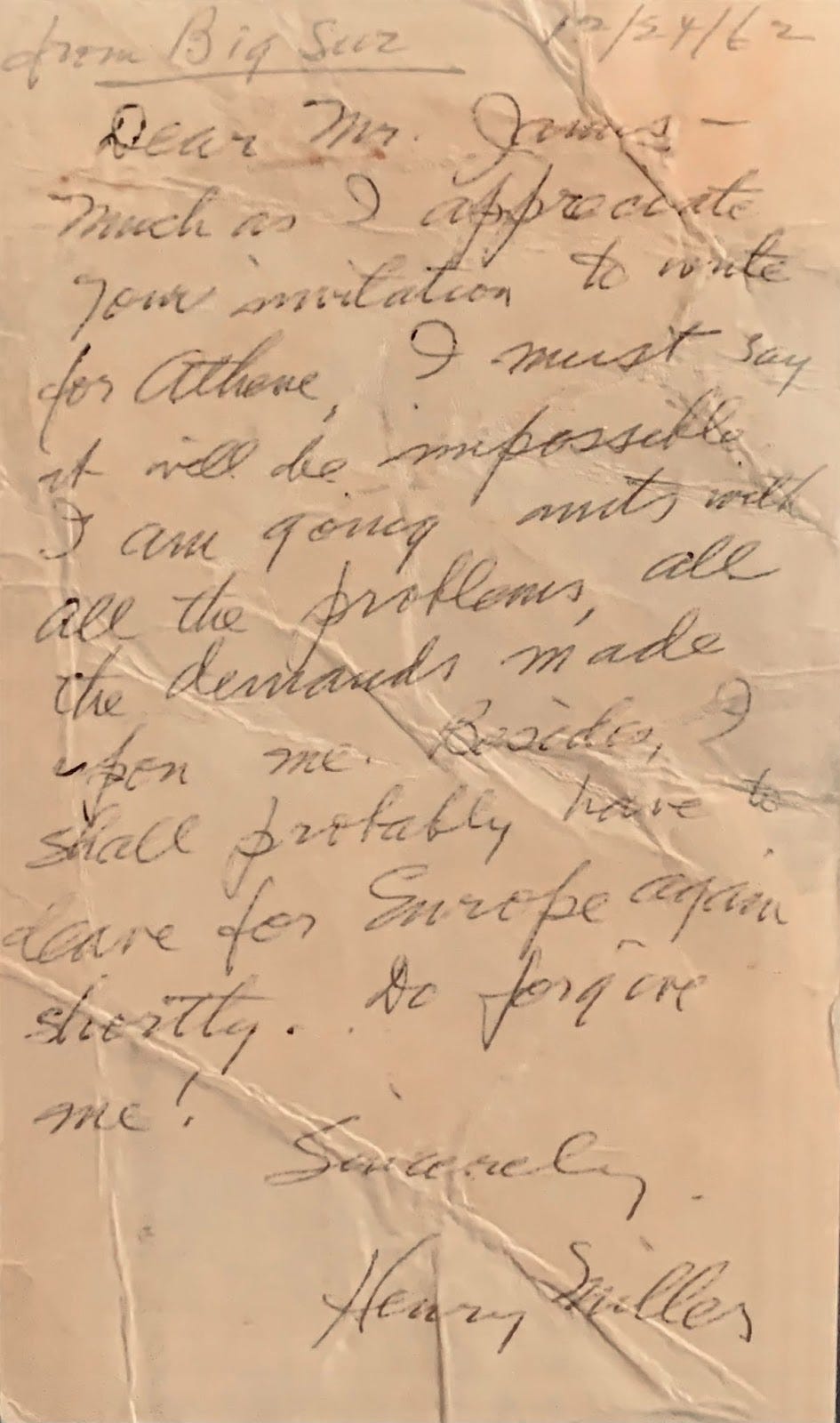

I have the postcard pictured below — handwritten by Henry Miller, declining a writing assignment — framed and sitting near my desk. There’s something kind of wonderful about it. He expresses frustration with responsibilities, but also that, well, I may just have to go to Europe because that’s what I do. “I am going nuts with…all the demands made upon me,” he writes. “Besides, I shall probably have to leave for Europe again shortly.”

I keep it as a reminder. But it’s still a challenge — in which I frequently fail. You admit in a footnote in your afterword — which is a great bit of writing and insight into your process, by the way — that you could do a better job yourself of keeping the main thing the main thing. I definitely would not have guessed that about you. Why do you say that, and what are you doing to remedy it?

RH: I actually just bought at an auction this little memo from the Truman White House. His secretary is writing, “Should we say that due to too many requests, the President must decline?” And Truman underlines that sentence and says, “The proper response is underlined,” and signs his name. I have that next to two pictures of my kids. I just like the reminder that when I am saying yes to random stuff, I am saying no to very important stuff (them!), to say nothing of my writing. So yeah, I do struggle with it. Especially when there is a dollar sign attached to the request. That’s easy to quantify. It’s harder to calculate what a couple extra days fiddling with a manuscript might get you. It’s harder to predict how it’s going to impact the vibe at home or just your general happiness. I’m generally pretty disciplined, but maybe it’s more like the quality of the food an athlete eats. Like, they’re going to be pretty damn good, even if they eat McDonald’s. But if they’re really optimizing their nutrition, they’re just going to operate on another level. I found during the pandemic, all I had was family, work, and then surprisingly some me-time too. There were no meetings, no travel, no cool exciting shining things. So I was monkishly productive…and also monkishly happy. I’m trying to preserve that as much as I can as we get further and further from those days.

Thanks to Ryan for his time, and thank you for reading. Let me know below what you thought of the image-centric Q&A format.

For more, check out Discipline is Destiny.

And if you enjoyed this post, please share it.

If a friend sent this to you, you can subscribe here.

Until next time…

David

I really enjoyed the conversation floating around and near to the book and it’s literal text, but also it’s distance from it. This felt fun and different and interesting. Keep trying new things!

What I like about your interviews, David, is that both sides are worth reading and have something to say.

In many interviews the question is weak, or repeats any other interview, or is antagonistic.

Yours are more of a conversation. I enjoy them.