A Technique Championed by Russian Writers (And Fraggles) Can Give You a New Perspective

"Defamiliarization" frames usual things in unusual ways

Welcome to Range Widely, where I help you step outside your lane for a few minutes each week. You can subscribe here:

and see previous posts here. Feel free to join the conversation; I've enjoyed responding to comments!

Last week, I wrote about a new study showing that broad exploration precedes impactful work. This week, I want to discuss a simple kind of personal exploration that anyone can try for a new perspective. It’s called defamiliarization.

I was introduced to the concept by Angela Chen (whose Twitter feed regularly fascinates me. Seriously, definitely worth a follow.). Angela shared the following example from a “Freakonomics” podcast, in which a professor gives his students this fictional Shark Tank pitch:

“I’d like to open a new kind of grocery store. We’re not going to have any branded items. It’s all going to be private label. We’re going to have no television advertising and no social media whatsoever. We’re never going to have anything on sale. We’re not going to accept coupons. We’ll have no loyalty card. We won’t have a circular that appears in the Sunday newspaper. We’ll have no self-checkout. We won’t have wide aisles or big parking lots. Would you invest in my company?”

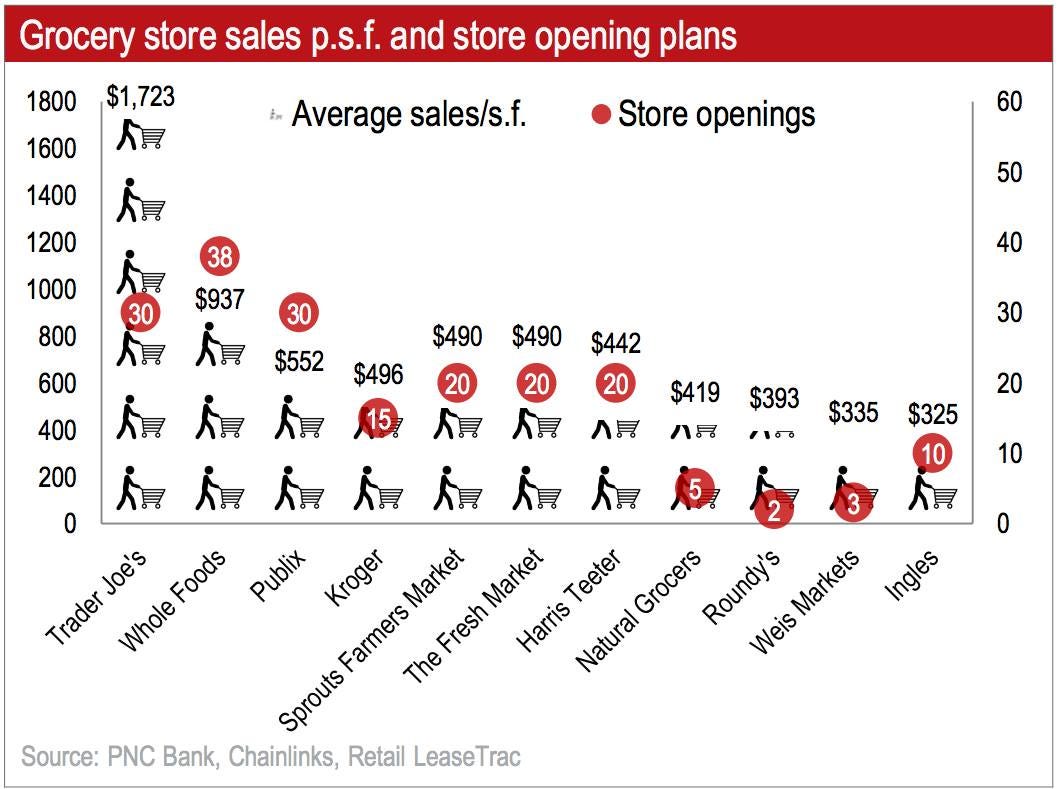

This isn’t a very appealing pitch. It’s also a description of Trader Joe’s — which has, by far, the best sales per square foot of any grocery store.

Angela highlighted this as an example of what a group of early twentieth century writers known as the Russian Formalists called “ostranenie” (остранение), or defamiliarization. They would describe usual things in unusual ways, thus providing a different perspective on experiences we normally take for granted. The idea was to “reawaken our senses by making the familiar unfamiliar,” as a Russian Formalist put it.

One of my favorite examples of defamiliarization comes from Fraggle Rock. (I’m transposing the term; the Russian Formalists didn’t have Fraggle Rock, sadly for them.) If you don’t know Fraggle Rock, (sadly for you), it was a 1980s TV show created by Jim Henson that featured several communities of Muppet-like creatures living in underground caves and navigating life challenges.

Gobo Fraggle was the main protagonist, but my favorite character was his relative — Uncle Traveling Matt. Uncle Traveling Matt had decided to venture out from the caves, through a mouse-hole in the wall of a house above, and was now exploring “Outer Space” where the Silly Creatures live. (That would be us.) Uncle Traveling Matt would send Gobo postcards about his experiences in Outer Space, and the show would depict scenes of those experiences as Gobo read the postcard aloud.

On his first adventure to Outer Space (video below), Uncle Traveling Matt blithely walked into traffic. When cars started honking, he assumed they wanted to communicate, and began trying to learn their discordant language. "Fortunately, I have an excellent ear for foreign languages," Matt says, as the frustrated drivers laid on the horns.

It’s silly, sure, but I think Uncle Traveling Matt was a brilliant form of defamiliarization: a way to make viewers think differently about things they barely notice anymore.

Defamiliarization reminded me of a chat I had with Nest co-founder Tony Fadell; Fadell said that we often miss opportunities because we’re habituated to the status quo, so look right past familiar items. Most of us look right past thermostats, but Fadell saw a tool long overdue for change. (His TED Talk, “The first secret of design is...noticing,” is worth a watch.)

When I worked as a fact-checker earlier in my career, a colleague gave me the excellent advice to go backward through any article I was checking, ticking off each fact as I went. When I only went the usual direction, I found I always just unconsciously glanced over something.

These days, when I’m stuck in my own work, rather than banging my head against the same wall, I try to get a different perspective. That could be as simple as switching from writing on a computer to longhand, or from writing to drawing if it’s relevant, or even just going for a run — which is remarkably effective at giving me new ideas when I’m stuck. (I just have to make sure to carry something to record them with, because ideas go as easily as they come when I’m running.) I also have a little couch in my office that faces the opposite direction of my desk chair; I’ll flop onto that when I need a shift of perspective (and body position!).

I’m sure I’ll return to this issue, but since Angela attuned me to it, I’ve collected a few examples of how some other people practice defamiliarization. So I want to share a few of those, in case you’re in need of a quick frame-shift and are looking for inspiration. Some are elaborate, and others very simple.

Many of the examples below are from writers because, well, I personally look for tips from writers. But I stuck a few examples from other domains at the bottom, in the hopes of getting your brain gears turning.

First, The Writers

-Novelist Eudora Welty would pin passages of her stories to her bed so she could see the work as a whole, and then edit by moving the pins around, as if rearranging a quilt.

-Rather than the bed, journalist Gay Talese pinned his drafts to the wall, walked across the room, and looked at them through binoculars. “I want to look at it fresh, as if somebody else wrote it,” he told Robert Boynton for a book on nonfiction writers. When a new office was too narrow for that, Talese instead printed a copy of his draft with each page at one-third the size, to create that “same distorting effect.”

-Journalist Jane Kramer told Boynton that she would move between the US and Europe, “alternatively leaving one and reintroducing herself to the other — a dialectic that keeps her perspective toward each fresh and open.”

-Novelist Jhumpa Lahiri abandoned her native language entirely in order to gain a new perspective.

-Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami developed his inimitable style by ditching his familiar language more briefly: he labored to write a first draft in English, and then translated back into his native Japanese.

-Leo Tolstoy used narrative techniques to defamiliarize for his readers. In “Shame!” Tolstoy describes public flogging without using the term “flogging,” in order to force readers to think in detail about what’s actually happening. And in his short story “Kholstomer,” readers are surprised to find out that the narrator — who was providing perspective on human social conventions — was an old horse.

-In simpler interventions (akin to me going for a run), Philip Roth would write a sentence or two, and then “turn it around. Then I look at it and I turn it around again.” Then he’d have lunch, and come back to it; then he’d have tea, and then come back to it; then he’d lie down and think, and then come back to it. In other words, he used frequent breaks so as not to fall into a routine perspective.

And Then, Well, More Writers — But Some Other People Too!

-In the only formal art class he ever took — which he dropped out of — Dr. Seuss rotated his paper to work on still life upside down. (According to his biographers, the teacher was not pleased: "No, Theodor. Not upside down! There are rules that every artist must abide by. You will never succeed if you break them.")

-Artist (and author of Steal Like an Artist) Austin Kleon suggests “borrowing a kid” to get a new perspective on scenery you take for granted.

-Sculptor Rachel Whiteread captures “negative space” by making molds of the air inside or around structures, like houses and staircases. I saw one of her exhibitions in person, and it definitely fired a few new synapses (it's an expression) for me in terms of thinking about physical space.

-Jazz pianist Dan Tepfer records Bach and then electronically flips the entire piece upside down. (The practice of “inversion” in musical composition has a long history. And if you want to hear a pianist play famous pieces on a flipped keyboard, check it out.)

-Similarly, when he was a child, legendary composer Robert Schumann would flip pages of music upside down to search for new patterns.

-New York Times reporter Benedict Carey, author of How We Learn, suggests that our ability to learn new things can be hampered by routine. Thus, he advises, we should make sure to change our daily routines in small ways, like altering our workspace a bit, or taking a different route to work — which the executive vice chairman of the New York Stock Exchange apparently already does.

-For a simpler exercise, you might try reversing time in your mind when you consider an issue.

-Ryan Holiday notes how near-death experiences change our perception of the usual things, and recommends the Stoic practice of memento mori — consciously thinking about your mortality — to capture some of that (without the “near-death experience” part).

-And finally, one of my favorites: we give better advice to others than to ourselves; so when you’re in need of good advice, find someone else to give it to, and you’ll end up helping yourself.

I’d love to hear other suggestions, so please share thoughts in the comments. Maybe this can be a fun creative exercise.

And if you enjoy this newsletter, please share it. You can find this post, and all previous posts, here.

Thank you for reading. Until next week…

David

P.S. I mentioned Austin Kleon above; I'm a huge fan of his work, and I'll be in live discussion with him later this month — info here. Come check us out! And for more widely ranging thoughts throughout the week, you can follow me on Instagram and Twitter.

I might try this writing about a patient-doctor encounter… so many parts need to be turned upside down, it’s almost too easy! Thank you for the intentionally warped perspective

Hey david. My first time here and if this is the sample then so looking forward to the other reads. Defamiliarisation as a tool to creativity and the route to innovation is to first notice really stuck with me. Planning to change my work area tomorrow in the hope 😀