With the exception of state-owned banks in China, JPMorgan Chase is the largest bank in the world. And growing.

JPMorgan recently struck a deal to acquire the deposits and most of the assets of First Republic Bank, which was seized by regulators as it headed for collapse. According to the New York Times, First Republic “is the second largest U.S. bank by assets to collapse.” The first largest: Washington Mutual, “which failed during the financial crisis of 2008 and was also acquired by JPMorgan.”

With all this JPMorgan news, I bring you (in very brief) the fascinating origin of America’s largest bank…

In the 1790s, New York City suffered a yellow fever outbreak basically every year. The mechanism of disease outbreaks (cholera was another common one in cities) wasn’t understood, but somehow people realized that having stagnant wastewater sitting in gutters wasn’t great, and that clean drinking water would be nice. So the city’s Common Council proposed a publicly constructed water system.

Enter former New York attorney general; former U.S senator from New York; former (unsuccessful) vice-presidential candidate; and newly minted head of the New York State Assembly: Aaron Burr — part of a group of newly elected anti-Federalists.

Burr pushed a proposal made by his doctor brother-in-law, Joseph Browne, to privatize water delivery. Browne proposed a company that would pipe fresh water into Manhattan from the Bronx River and charge households $10 per year for 30 gallons of daily fresh water. (If a household only wanted access to water for use in firefighting: $2 per year.)

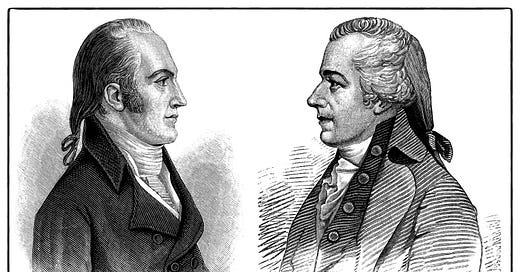

In order to convince the Federalists on the Common Council, Burr “enlisted his archrival, Mr. Federalism himself, Alexander Hamilton, as an ally,” as economist Edward Glaeser put it. Hamilton was concerned that the city wouldn’t be able to pay for the project, and so got on board with a private company; the city would have the ability to buy a large chunk of shares, and to have representation on the board of directors. And thus, The Manhattan Company was authorized in the spring of 1799.

Except Burr managed to slip in some rather important changes at the last minute. (Guess Hamilton wasn’t in the room where it happened.) According to Maura Ferguson and Sarah Poole, who co-curated the Museum of American Finance’s “Ebb & Flow: Tapping into the History of New York City’s Water” exhibit, the crucial clause was in paragraph nine of the company’s charter:

“And it be further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the said company to employ all such surplus capital as may belong or accrue to the said company in the purchase of public or other stock, or in any monied transactions or operations not inconsistent with the constitution and laws of this state or of the United States, for the sole benefit of the said company.”

In other words, the water company could use surplus funds for financial operations of its choosing. By the fall of 1799, most of the company’s cash was being used for the Bank of the Manhattan Company. As Ferguson and Poole wrote:

“In effect, it provided Burr with a Republican bank to rival Hamilton’s Federalist Bank of New York.”

Whoops, Alexander.

The company didn’t end up fulfilling its water mission. Rather than piping in water from the Bronx, it used ground wells — some of which weren’t sanitary — and didn’t provide nearly enough water for a growing city. The company also didn’t repair streets after laying pipe, which led to a legal fight with the city. Ultimately, Ferguson and Poole add:

“Burr’s deception about his intentions to start a competitor bank with the Manhattan Company was one of the many disagreements between [him and Hamilton] that eventually led to the duel.”

It wasn’t until the 1830s that the Croton Aqueduct was created, and finally gave New York City reliable, clean water distribution.

For a final fascinating (and funny) paragraph, back to Ferguson and Poole:

“After the Croton System opened, the Manhattan Company waterworks emptied out and was torn down in the early 20th century. To maintain its state charter, water was pumped by a bank employee at the site every day until 1923. The Bank of the Manhattan Company is the earliest predecessor of today’s JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States. In 1965, Chase Manhattan was granted a federal charter that was no longer dependent on providing clean and wholesome water.”

Thank you for reading, and this is the part where I spare you a joke about underwater banks.

Instead, a quick Range Widely update: I recently started using Substack’s new “Notes” space. Thus far, it seems like a nice, moderately paced, non-bot-infested place to share links, excerpts of posts, and thoughts. If you’re interested, head to substack.com/notes or find the “Notes” tab in the Substack app. As a subscriber to Range Widely, you’ll automatically see my notes.

If you enjoyed this bit of banking/water history, please share it.

Range Widely is entirely reader supported. You can support this newsletter with a free or paid subscription. Either way, all content is free.

Finally: I’ve never been to the (Smithsonian-affiliated) Museum of American Finance, but someone just highly recommended it to me the other day, so I’m going to check it out next time I’m in New York City. If anyone has been, I’d be interested to hear your impressions in the comments below.

Until next time…

David

It's always crazy to know that almost all US institutions passed through the hands of like 20 people

Highly entertaining. Likewise, I am drawn more and more to these historical anecdotes. For me, they help explain the state of things today.

Heather Cox Richardson has an excellent blog on political history and today's events.

Thanks for putting this piece together!