The Truth About Creativity and Mental Illness

There is a grain of truth in the folklore, but the reality is a lot more interesting

Welcome to Range Widely, where I hope to help you think new thoughts. If you like thinking new thoughts — and you look like you do — you can subscribe here:

If you'd like to watch my (free) virtual chat with Annie Duke tomorrow night — about her new book QUIT — you can register here. Bring questions!

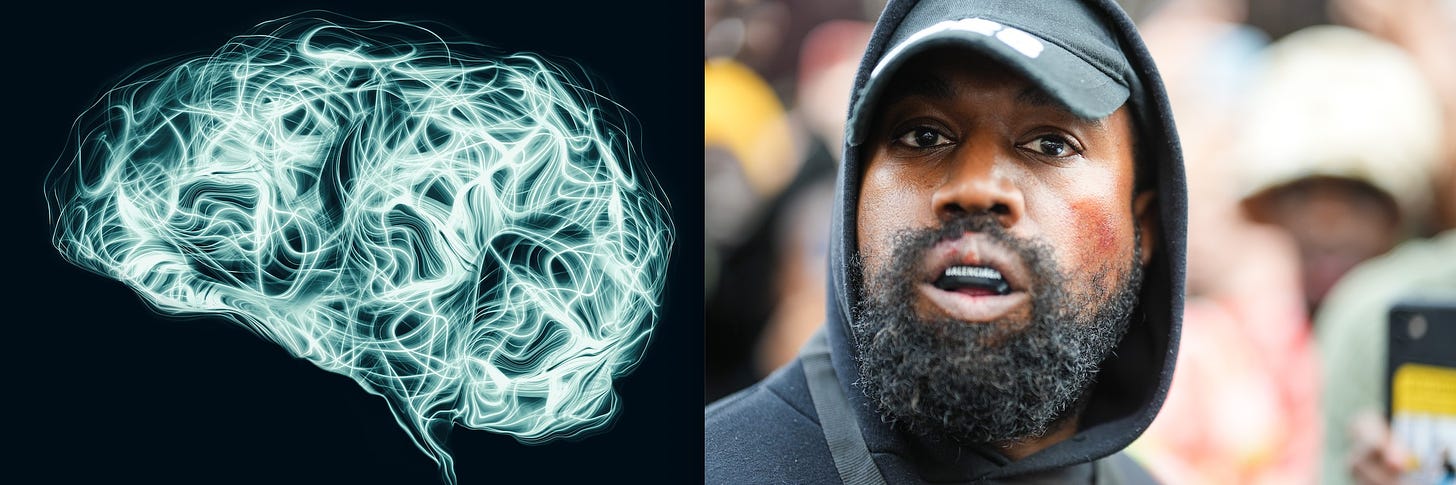

If you didn’t follow it (and lucky you), last week Ye (formerly known as Kanye West), tweeted that he was le tired, but that just as soon as he got some rest and woke up he would “go death con 3 ON JEWISH PEOPLE.”

I’m not going to rehash the context, which you can read here. Nor am I clever enough to get to the bottom of why he chose the median of (presumably) the DEFCON scale of military readiness. The DEFCON 3 box is yellow, so perhaps he was making a carefully considered literary allusion to the fact that it starts with ye? 🤔

Rather, my cold take for this week comes from seeing people on social media averring that Ye’s antics are a necessary part of his genius. Ye has said that he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and in the past has also said that he went off his medication in order to make better music. This made me curious: What does research say about the folkloric link between mental illness and creativity?

As it happens, a friend of mine — psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman — co-authored an article reviewing the evidence. Long story short, as Scott and his co-author Elliot S. Paul wrote:

“There is a grain of truth to the notion that creativity and mental illness are related, but the truth is much more nuanced—and we think interesting—than the more romanticized notions of the link.”

The most interesting report that Kaufman and Paul cited was written by Swedish researchers who were using a dataset that included information for 1.2 million people over 40 years. Looking across a bunch of creative professions in art and science, the Swedes found that, overall:

“Individuals holding creative professions had a significantly reduced likelihood of being diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, unipolar depression, anxiety disorders, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, autism, ADHD, or of committing suicide.”

So, on the whole, I think we can dispense with the idea that mental illness is a necessary component of creativity. But now for the nuance.

The one mental illness that was overrepresented in creative professions: bipolar disorder. But this was a small effect; bipolar disorder was only slightly overrepresented in creative professions, so the vast majority of creators in those professions would not have bipolar disorder. The profession where bipolar (as well as schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse) was most overrepresented: authors. So the news from this study for me and my colleagues was not great. Even authors with no diagnosed mental illness were at heightened risk of dying by suicide.

But again, across the many creative professions studied, individuals were overall less likely to have a diagnosed mental illness, and less likely to die by suicide than members of the control population. (Interestingly, the Swedish study also took a look, for comparison, at accountants, “one of the occupations with predominantly conventional qualities.” Accountants were not at increased risk of any of the mental illnesses in the study.)

Now for what I found to be the most interesting part of the paper: family members of creative professionals were more likely to have certain mental illnesses. In other words, a creative professional was more likely to have relatives with diagnosed mental illness, even though the professional themself was no more likely to have a diagnosed mental illness. The Swedish authors wrote that first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were overrepresented in creative professions, as were siblings of individuals with autism.

Interesting! Why would that be? Kaufman and Paul offer a theory:

“Could it be that the relatives inherited a watered-down version of the mental illness conducive to creativity while avoiding the aspects that are debilitating?”

How would that work? Let’s consider one possibility:

Say that the hypothetical Steele family has a history of schizophrenia. Most members of the family tree do not have schizophrenia, but some do. Let’s say that there are 100 different genetic variants in the Steele-family-tree DNA that increase the risk of schizophrenia. Family members with schizophrenia have 50 or more of those. Family members without schizophrenia inherited fewer than 50 of those gene variants. They do not have schizophrenia, but that genetic inheritance did confer some “schizotypal” traits. And perhaps those traits aid creativity, without developing into mental illness. (A recent study makes essentially this argument — "Genome-wide association study of school grades identifies a genetic overlap between language ability, psychopathology and creativity.")

Kaufman and Paul don’t use a genetic hypothetical, but they do delve into this idea of potential overlap in mental processes between creativity and mental illness. They cite, for example, research showing that people with schizophrenia, and their relatives, and creative people all had difficulty suppressing the precuneus — a part of the brain involved in creativity — while working on a task that scientists assigned them.

An inability to suppress certain brain functions while trying to complete an assigned task may sound annoying or unproductive, but “these findings are consistent with the idea that more creative people include more events/stimuli in their mental processes than less creative people.”

Kaufman and Paul add:

“It seems that the key to creative cognition is opening up the floodgates and letting in as much information as possible.”

The article goes on to describe other research, including that the personality trait of “openness to experience” is associated with both creativity and schizotypy. The article is filled with citations to scientific papers, but written for a general audience, so check it out here if this interests you.

I find all of this fascinating. And yet, I think my main takeaway is still this paragraph from the Swedish paper:

“We found no positive association between psychopathology and overall creative professions except for bipolar disorder. Rather, individuals holding creative professions had a significantly reduced likelihood of being diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, unipolar depression, anxiety disorders, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, autism, ADHD, or of committing suicide.”

And even for bipolar, the effect was small.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

And if you aren’t subscribed to Range Widely, you can do it here:

Thanks for reading. Until next time…

David

Illustration credit (brain): Sean Gladwell/Getty Images; Photo credit (Ye): Edward Berthelot/contributor/Getty Images

We have to be careful reading into these sorts of studies, and that care takes a lot of mental energy.

Physicians in biomedical research make this stretch all the time: just because there is a correlation between two traits, does not mean we have demonstrated the directionality or even tne direct nature of a causal vector between them.

"Even authors with no diagnosed mental illness were at heightened risk of dying by suicide."

The more commonplace use of "risk" is as in the term "risky behavior" - if you engage in it, then you increase the likelihood of a bad outcome because there is a direct causal link between the behavior and the outcome. More behavior, more likely outcome. People who smoke have a higher risk of cancer. People who drive while drunk increase the risk of losing control of a motor vehicle.

Writing for a living itself does not increase one's risk of dying by suicide. Living as a professional writer doesn't either. At best, there may be a common upstream causal factor that simultaneously tracks with both the likelihood of any given individual in a population both acting on suicidal thoughts, and also choosing to be an author over a lifetime.

This seems like nit-picking, but it's important to be precise about what the risk is. In the study cited, the risk assessed is a population-based one, the risk of drawing a sample with higher-than-expected numbers of writers and also higher-than-expected numbers of deaths by suicide. It's very easy to mistake that for a causal risk at an individual level: "As a writer, I risk dying by suicide and could avert this fate by becoming an accountant". Not the same. Which dovetails with Mark VanLaeys' point.

What if the expression of mental illness is "turned down or tuned out" by the mere act of venting through CREATIVE life work? Millions of people would love to do creative work for a living but only those with special talents tend to pay the bills that way. I wonder what's the incidence of mental illness in those who are especially creative but stuck in non-creative work that sucks out their time and energy