The Trouble With Heroic Individualism

A more realistic version of heroism works in literature and life

Welcome to Range Widely. If a friend sent this to you, you can subscribe.

If you’re new, check out the last post on building team culture.

And if you want to share this post, click the button below.

This post is unusual. It contains two linked parts. In the first part, I think out loud about a literary classic that has my brain gears turning. The second part is a Q&A with Brad Stulberg, author of The Practice of Groundedness, and it’s related to a topic in part one.

Because it has two parts, this post is longer than usual. But you can just scroll right down to the Q&A with Brad Stulberg on “heroic individualism” if you want. My musing in part one isn’t necessary for enjoying part two. Without further ado:

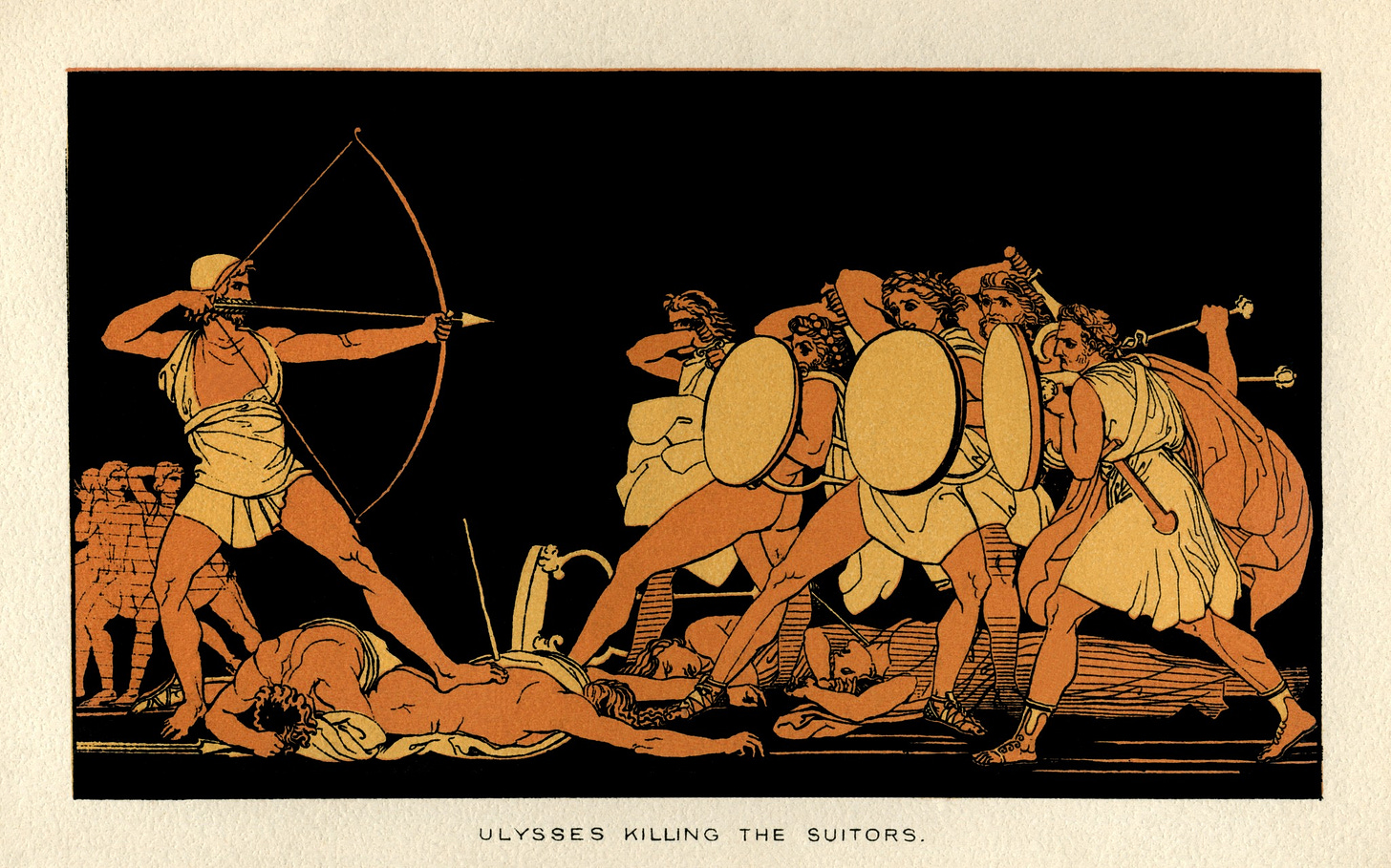

Part I: Ulysses and the Everyday Hero

Author Eric Barker (subject of a recent Q&A on relationships) recently pointed out to me that I seem to be on some kind of reading-the-classics kick, because when we’ve talked lately I’ve been reading Dickens, or Woolf, or Dante, or Shakespeare. I hadn’t realized I was on such a kick until he said it, by which time I had picked up James Joyce’s Ulysses (this edition). The chapter I just reread has really lodged in my brain.

Ulysses employs a parallel structure to Homer’s Odyssey. (“Ulysses” is the Roman name for Odysseus.) Joyce clearly admired The Odyssey, and its multifaceted main character. After all, he apparently saw in it elements so universal that he could transpose them to 20th century Dublin. That said, I can’t help but notice how Joyce frequently (and often hilariously) parodies hero mythology.

Let me give an example from chapter twelve. Each chapter corresponds to some episode in The Odyssey; chapter twelve is linked to the part in which Odysseus blinds the man-eating cyclops Polyphemus by sticking a burning spear in his one giant eye.

A main character in chapter twelve is known to readers only as “the citizen.” He’s a former national shot-put champion turned super jingoistic nationalist. He spends his time carping about Jews and Englishmen and mythologizing Irish glory, while waiting for others to buy him drinks. (Sidenote: The social requirement of reciprocating a round of drinks led to the founding of St. Patrick’s Anti-Treating League in 1902. It didn’t push sobriety, but rather sought to curtail the escalating pyramid-scheme custom of round-purchasing as friends joined friends at the pub.)

At one point while the citizen is sitting at the bar, he roughly handles a friendly dog. The narration then immediately breaks from the scene and launches into a two-page bombast describing what seems like a gigantic (shot-putter like) Irish patriot. The description is purposely over the top. The patriot’s nostrils, for instance, “were of such capaciousness that within their cavernous obscurity the fieldlark might have easily lodged her nest.” His accouterments include stones graven with images of Irish heroes. Except, the page-long list of heroes drags on to include non-Irish figures, some of whom it appropriates by (satirically) tacking Irish first names on famous last names — “Patrick W. Shakespeare, Brian Confucius, Murtagh Gutenberg.” By the end, the list lays claim to Captain Nemo, Adam and Eve, and the Buddha.

The joke, I think, is that a certain brand of nationalism — personified here by the brutish, falsely heroic citizen — manifests as intense hero-worship, to the point that it claims a preposterous array of figures as part of a heroic lineage. The technique recurs in the chapter. The effect is to lampoon the poor behavior of the citizen and others who view themselves as the only true patriots, or who want to claim an exclusive heritage for themselves while blaming their problems on those they see as outsiders. This contrast of reality with mythology — ancient and contemporary — is all over Ulysses, albeit usually in more subtle form.

Homer’s Odyssey follows the brilliant and handsome Odysseus, who arrives home after an epic ten-year journey and reclaims his wife by shooting an arrow through the holes in twelve axe heads. The main protagonist in Ulysses, on the other hand, is homeward-journeying advertising-canvasser Leopold Bloom, who does his best to navigate the indignities and desires of a single Dublin day. We can see both Odysseus and Bloom wrestle with variegated roles — husband, father, lover, and more. But, at least to me, only Bloom feels real.

If part of Joyce’s own modern myth-making was to write a new kind of national epic, I think his mythology celebrates human foibles and adaptive values, including social flexibility and cultural tolerance. Bloom comes off as an empathic man; a pacifist; something of an outsider to the good ole’ boys network; very curious about science, but only mildly knowledgeable; grappling with his own contradictions; and full of inner thoughts that his peers would criticize as feminine. He is rarely brave in conventional terms.

And yet, he feels heroic, at certain times, in much subtler and more realistic ways than Odysseus. He is heroic in the small ways that all we who can’t fire an arrow through twelve axe heads can be heroic. Where Odysseus blinds the cyclops with a flaming spear, Bloom merely shakes a smoldering cigar during an argument with the enraged and culturally blind citizen. Where Polyphemus threw a boulder at Odysseus, the ex-shot-putter citizen hucks a biscuit tin at Bloom. As the Irish scholar Declan Kiberd put it, Joyce’s impulse “was always to scale grandiose claims down to a human dimension, to domesticate the epic.”

This is probably a good time to note that people have spent entire careers analyzing Ulysses, whereas it took me oh, about 300 pages to realize that there were two different omniscient narrators often operating at the same time. So, ya know, take my interpretations with a shaker of salt. But reading chapter twelve, with its satire of individual heroics, reminded me of a book I read precisely one year ago, by a writer whose wisdom I really value.

In The Practice of Groundedness, Brad Stulberg writes about — and stridently criticizes — the notion of “heroic individualism.” James Joyce didn’t immediately respond to my request for an interview, so I invited Brad to expand on heroic individualism in the present day…

PART II: The Way of Groundedness

David Epstein: So Brad, I’ve followed your work for years, and I think you’re conceptually in line with the Joycean approach of “domesticating the epic” that I mentioned above. What I mean is that, increasingly, I’ve noticed you attacking inflated claims about super-diets and super-supplements and super-workout routines and super anything that promises a quick fix to all that ail humans. Am I right in perceiving that you’ve become more public about doing that? If so, why?

Brad Stulberg: Yes, I think that’s an astute observation. I do not want to become a cynical person, so my rule of thumb in my writing is to focus on building up ideas 90 percent (or more) of the time. However, sometimes ideas need to be broken down, and one of those is this relentless focus on “optimization,” and, more broadly, what I’ve come to call bro-science: the complexification of everything into biohacks and productivity hacks and personal improvement hacks. If any of that stuff genuinely worked I’d be using it myself and recommending it. Unfortunately, it doesn’t. A lot of well-meaning (and often very smart) people get sucked into the wellness and performance treadmill of trying one thing after another and finding themselves in an endless cycle of longing and striving for a fix that doesn’t exist.

What does work is nailing the basics, which tend to be simple, but not always easy. So much of my writing, and especially the book I know you love, The Practice of Groundedness, is about giving people an awareness of the pitfalls we too easily fall into. And then, the part about building ideas up is communicating what actually works to feel and do better, and supporting my readers and walking the path with them as they try to define and live a life of excellence and well-being.

DE: One of the things I appreciate about your thinking is that you’re masterful at framing the basics in ways that help people remember and be inspired by them, without recourse to exaggerated mythology. As you just pointed out, the best ways to improve ourselves are often simple to understand but difficult consistently to do. Can you expand on what you mean there, and give an example?

BS: In the book, I call this the “knowing-doing gap.” First, you’ve got to know something and be convinced that it’s meaningful, valuable, and effective. Then, you’ve actually got to do it. So many books (and good ones, too!) focus mainly on the former, on knowing. But reading a book is not the same thing as applying what you’ve learned. I try to emphasize the latter – doing — as well.

You wanted a specific example, so let’s take presence. As a writer, my first job is to use modern science, ancient wisdom, and day-to-day practice to show the value of being present for feeling good and doing good — my shorthand definition for excellence. Then, I’ve got to help readers understand that actually doing presence depends on concrete habits and actions. For instance, maybe every evening at 7 PM you turn off your phone, put it in a drawer in a room that you don’t go into, and don’t take the phone out until 7 AM next morning. You go from presence being a key source of enlightenment (it probably is, by the way) to putting your iPhone in your sock-drawer, or, if you’re an addict like me, having your partner hide it from you and instructing them not — under any circumstance — to tell you where it is.

DE: Haha…Since I was writing in part one of this post about Odysseus, I feel obliged to point out that you’ve just described the modern version of having your crew lash you to the mast so that you won’t be lured by the sirens. …And on that Odyssean note, let’s talk about “heroic individualism.” Can you first define it for us?

BS: Heroic individualism is my term for so much of what ails us as both individuals and as a society today. I define it as:

a significant game of one-upsmanship against both self and others where measurable achievement and status are the main arbiters of success, where optimization is only thought of on short-term scales, and where the goal post is always ten-yards down the field.

With heroic individualism, you think that if you just do this one thing then you’ll finally be happy, whole, content, and so on. But it’s an illusion.

DE: That kind of reminds me of, say, when people feel the need to summit Mt. Everest to cure a midlife crisis. I think whatever ailed them is probably still going to be there when they get down. So what’s a better way to think about this?

BS: You’ve got to find a way to create positive qualities in the now, in the process of striving for goals, otherwise you’ll never get them. As Robert Pirsig, author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, once said: “The only zen on the top of mountains is the zen you bring up there.” Modern psychology agrees.

DE: Can you share the signs or symptoms of heroic individualism?

BS: Here they are, straight out of the book:

Low-level anxiety and a sensation of always being rushed or in a hurry — if not physically, then mentally.

A sense that your life is swirling frenetic energy, as if you’re being pushed and pulled from one thing to the next.

A recurring intuition that something isn’t quite right, but unsure what it is, let alone what to do about it.

Not always wanting to be on, but struggling to turn it off and not feeling good when you do.

Feeling too busy, but also restless when you have open time and space.

Easily distractible and unable to focus; struggling to sit in silence without reaching for your phone.

Lonely or empty inside.

Struggling to be content.

Successful by conventional standards, yet feeling like you’re never enough.

Wanting to find some inner calm and peace.

DE: I have to say, I can think of periods when all of those applied to me. “Feeling too busy, but also restless when you have open time and space” isn’t something I’ve articulated that way, but have definitely felt, and I’m glad to sort of have a label for it so I can identify it. What do you think in general about the importance of being able to name or label these kinds of symptoms, so to speak? I know there’s a “name it to tame it” idea in psychology, where identifying your emotions can help you manage them.

BS: Once you can name something it gives you a certain kind of power over it and the ability to do something about it. A big part of my goal for the book was giving people a language for things they may sense, feel, and intuit but don’t necessarily have words for. If I can give people a language, then I’m doing my job well.

DE: Now that we have a sense of the manifestations of counterproductive heroic individualism, I want to talk about — to use your term — “groundedness.” Your definition of it is, essentially, an internal strength and confidence (based on evidence) that sustains you through life’s ups and downs. It means identifying your core values, and explicitly living in alignment with them through the projects you choose, the interests you pursue, and the way you prioritize your time. You establish sturdy roots, in a sense, that serve as a constant amid change. Importantly, I think, you’re not framing groundedness as antithetical to ambition, but rather as making your productivity more sustainable and less frenetic, less focused on the hot new trend, and more focused on living and working in alignment with the values that you’ve explicitly identified.

And you’ve told me that, in hindsight, if you could change one thing about your book, it would’ve been to write more about what a “grounded society” would look like, as opposed to focusing on individuals and organizations. So can you share here what that would look like?

BS: It comes down to five core principles — and you’d take the same approach to organizational and individual groundedness, too.

Accepting and thoughtfully evaluating tradeoffs and making deliberate decisions and adapting. (In the case of society as a whole, ideally by incentivizing new technologies that make growth more sustainable for the planet and the lives of the people who live on it.)

Supporting presence and productive activity by encouraging and making participation in craft, sport, and the arts financially feasible for all. Also, supporting the health and safety of people working in the age-old crafts upon which we all depend, such as medicine and teaching.

Playing the long game: evaluating “success” and “failure” on time horizons that reach beyond a single quarter, and understanding that what looks “efficient” and “optimal” today may be destructive in the future. This is such an important point, Dave, and one that you and I have talked about in private, so we might as well emphasize it here. Whenever you mention being efficient or productive, you’ve also got to consider the time scale. What is super efficient and productive over the next 24 hours may not be sustainable, and thus efficient or productive, over the next 24 years. I could drink a ton of Red Bull and not sleep and write a lot of words over two weeks, but it wouldn't be an “efficient” way for me to craft a career as a writer. This is one of the ultimate traps of heroic individualism.

Realizing vulnerabilities and addressing them instead of kicking the can down the road — again and again and again — and in turn dealing with acute crisis after acute crisis. In the West, this would require an authentic reckoning with a history of enslavement and discrimination. At some point, we’ve got to have the family therapy session(s) instead of all this projection and tribalism.

Encouraging and supporting deep community and belonging instead of everyone going at it alone — sometimes out of necessity to make ends meet, other times because the ethos is so strongly pointed toward keeping up with the Joneses.

DE: I want to go back to our daily mythology for a second. I don’t want to blame everything on social media, but I do think it’s hard to avoid the influence it has on discouraging a sense of presence and on encouraging short-term ideals of success. How do you deal with (or suggest others deal with) the way that we’re digitally consuming the lives of people who are projecting infinite happiness and attractiveness — which gives people the frenetic FOMO that is the opposite of feeling present and grounded where you are?

BS: I remind myself it’s all performative kabuki and once it gets annoying I unfollow them.

DE: Ah. Fair enough. Seems like good advice. And on the advice note, you’ve actually reminded me of an unrelated piece of advice you espoused that I took to heart: to get involved with some real live Homo sapiens in my community. I acted on that one by joining the board of a phenomenal early childhood education center focused on poor families in my area. I’ve definitely found it challenging; it has led me to do some event logistics — not my strong suit. But I’ve also found it uniquely rewarding, often even more so than volunteering I’ve done with much more prominent national nonprofits. Please explain.

BS: I’m so glad you said this! Here’s the deal: at the risk of sounding woo-woo (though decades of psychology research and clinical practice support this) we are looking for love in all the wrong places. When we are intimately involved with other human beings in the real world, working on meaningful projects, having meaningful conversations, and striving toward meaningful goals, we don’t feel the need to go on the internet to look for status, validation, and love there. You know when people, myself included, get sucked into the social media retweet, “like”-and-comment game? When we are lonely. I’ll put my own skin in the game here. There is a direct correlation between my inclination to go fish for status on social media and how much time I’m spending with my neighbors, friends, training buddies, or out in nature. When I’m doing that other stuff I feel no need to fish for validation on social media. Me getting sucked into social media is a sign I’ve focused too much on “optimizing my brand” and not enough on being a wholesome human in the world. The pull into social media is a great corrective, actually.

DE: I assume you mean because it helps you notice that something is going wrong. And, since you brought up your own challenges, in The Practice of Groundedness you were really open about your own OCD diagnosis. You described the experience and treatments, and got into the research behind those treatments. I was wondering if you can super briefly share what happened with Range Widely readers, and tell us where you are on that journey now?

BS: To be completely honest, I can’t really share “super briefly.” It wouldn’t do the experience justice. OCD is extremely misunderstood by so many people, myself (at least at first) included. I was quite sick for a period of time. I am very fortunate to have gotten great help. Currently, I am in a solid spot. It was a really shitty year for me about five years ago. Ever since then, OCD has been an increasingly small part of my life. Today, I don’t really think about it much, if at all. If folks read the book they’ll learn a lot more about my personal story with OCD and secondary depression, but it’s a testament to the value of therapy, medication, getting help when you need it, and the fact that severe mental illness can strike like lightning but, with appropriate care and patience, it can also get better.

DE: Thank you for that. …And please allow me just one more abrupt left-turn in this Q&A: one of the Range Widely readers, William Murphy, who is interested in a great many things and leaves excellent comments on posts, left a question on the last post that I wanted to pass on to you. Here’s what he wrote: “I'm in a bad reading phase currently! Struggling to concentrate. Any quick fixes to help me improve my focus on getting back into it?” I made a few suggestions. I know you read a ton, and I know you’ve mentioned the ability to focus as a competitive advantage. While I know you’re not a “quick fix” guy, can you share any tips?

BS: Schedule it. Give yourself at least thirty minutes a sitting, as it can take time to groove into a rhythm. Treat concentration like a muscle that is out of shape; it might not feel great at first but, with time, the fitness to focus on reading will come back. Use a hardcopy book. Keep your phone out of the room. And read with a notebook nearby: this way, when random thoughts, some of which are important, pop into your mind (e.g., “My partner asked me to get chunk-light tuna from the grocery store; I forgot last time; I’d better get it tonight.”) you can write them down, offload your brain, and return to the book.

DE: Any last wisdom you’d like to leave us with? This can be anything, something you’re trying out, learning about, or want everyone to read.

BS: We are not minds or bodies or even minds and bodies. We are mind-body systems. All the latest research points toward this conclusion. René Descartes got some things right, but this one he got wrong. We didn’t get into it in this discussion, but in the book there is a chapter on physical practice and movement for this very reason. There was a long back-and-forth with my editor about including it, because what does physical practice have to do with qualities like acceptance, patience, presence, vulnerability, and community? But the answer is kind of everything. But if you read the book, you’ll see that physical practice looks a lot different than how most people think of “exercise.”

This was great, Dave. I love you man. I really do. I am so fortunate to call you a friend and thought partner!

DE: Descartes also got his theory of how we experience pain partly wrong, also by undervaluing the brain-body system. He theorized that threads in the body are moved by a stimulus, and the sensation of pain is directly proportional to that stimulus, "just as by pulling at one end of a rope one makes to strike at the same instant a bell which hangs at the other end,” he wrote. Turns out, how our brains interpret the meaning of the situation that caused the pain has an enormous impact on how we feel it, irrespective of the actual stimulus.

But now I feel like a jerk for responding to your heartfelt statement with a Descartes critique! I want to end on encouragement instead. So: please keep up the great and important work, personally and professionally.

BS: I love you in part because of your wealth of knowledge and ability to connect things, so here’s to Descartes being wrong about quite a bit, actually. He totally missed the boat on the nervous system being a thing, which turns out to be a pretty big boat for how we humans experience the world...

Thanks to Brad for this back-and-forth. If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

For more wide-ranging thoughts, you can follow me on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, or LinkedIn. If a friend sent this to you, you can subscribe below.

Thanks for reading. Until next time…

David

[image credit: whitemay/Getty Images]

David, thanks for posting this. I've been thinking a lot lately about he cult of individualism, specifically the cult of the leader and the cult of the hero. (In fact I've been using the second two terms interchangeably.) I have been writing about it here https://getshiftdone.substack.com/p/bankman-fraud, and would love to collaborate