The "Lesson I Have Learned" Mindset

Daniel Kahneman changed our thinking about thinking, and also changed his mind

In the fall of 2015, I got an unexpected e-mail introduction: an acquaintance was putting me in touch with psychologist Daniel Kahneman. Kahneman, who passed away last month at the age of 90, was awarded the Nobel prize in economics in 2002 for his work on the mental shortcuts that people use to make decisions with imperfect information.

Apparently Kahneman attended an event where I had given a brief talk. It got him interested in my book, The Sports Gene, and he wanted to connect. I had read Kahneman’s 2011 best seller, Thinking, Fast and Slow, and found it enthralling.

The book details decades of research on how humans make decisions, and how those decisions often deviate from economic models of rational actors. For example: Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky demonstrated that losses loom larger in our minds than do equivalent gains, which has a huge impact on our decision making. Because of this bias, if I offered Range Widely readers a coin-flip in which they win $100 if it’s heads, and lose $80 if it’s tails, many readers would decline to participate even though it’s a great deal, because the prospect of the loss feels more important than the prospect of the gain. Kahneman and Tversky gave this particular decision-making bias the now-famous moniker: loss aversion. In a more important scenario, loss aversion leads many people to underinvest in retirement accounts (or to invest too conservatively) because the pain of losses is so acute, even if they’re only short-term.

After we connected on e-mail, Kahneman invited me to lunch. Given that my idea of fun is talking to people about research, or about their work, and given that here I could do both with a Nobel laureate, you can imagine how hard-to-get I played for this date.

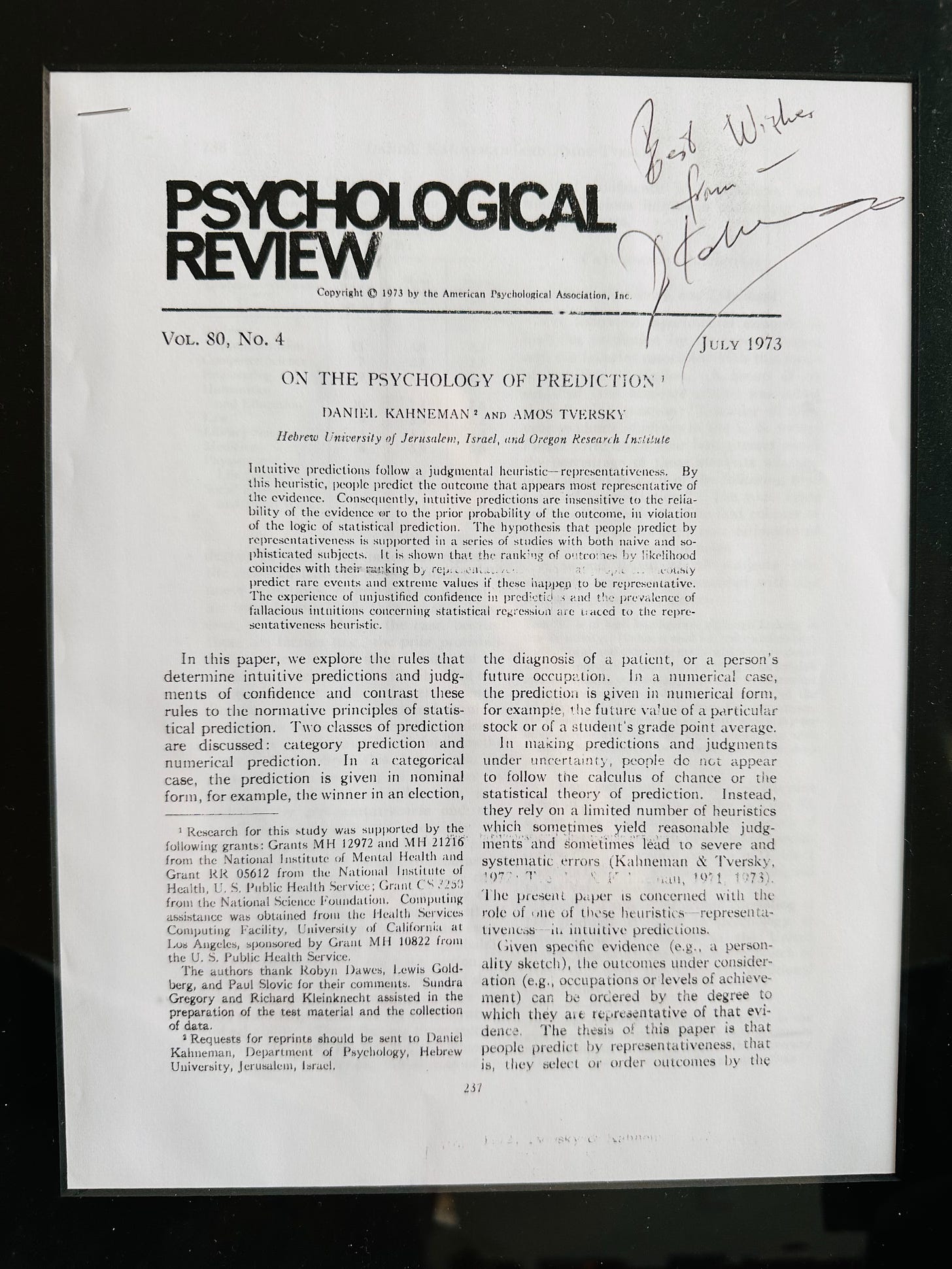

In preparation for lunch (that’s a thing), I read some of Kahneman’s papers, including one that was especially fascinating titled On the Psychology of Prediction, published in 1973.

The core point of the paper is that people make predictions based on “representativeness” — basically how close the details of a scenario fit a preconceived story in our heads. Predictions tend to ignore how reliable those details are, as well as any statistical evidence.

In the first experiment in the paper, Kahneman and Tversky gave statistically literate psychology students a description of a fictional high school student named “Tom W.” It portrayed him as very intelligent, tidy, and enjoying corny puns and sci-fi. The psychology students were told that Tom W. is now in graduate school, and asked to predict how likely it was that Tom W. was a grad student in each of nine different areas. Long story short: the predictions unfolded precisely according to how well Tom W. fit the stereotype of a particular domain, and completely ignored available statistical evidence. The psychology students said it was most likely that Tom W. was a computer science graduate student, even though, in 1973, there were few computer science graduate students.

The psychology students didn’t use statistical evidence about the rarity of computer science students to adjust their predictions whatsoever. Instead, they relied only on the superficial description of Tom W. from high school. This is not to say that the description should be ignored, only that the statistics should also be considered.

Thirty years later, Michael Lewis’s book Moneyball would make the same fundamental point: baseball scouts were making predictions based on how well an athlete fit a preconceived story (like how they looked), while undervaluing statistical evidence.

I printed out a copy of the paper and brought it to lunch to discuss. Kahneman told me that it was his favorite paper, so I asked him to sign it.

After that lunch, I emailed with Kahneman on occasion, and talked to him one more time about his research, which subsequently showed up in chapters one and five of Range. Mostly, I followed him from afar. That included when he ran into a bit of controversy in his field.

One chapter in Thinking, Fast and Slow focuses on social “priming” research — studies that investigated how a seemingly inconsequential stimulus dramatically alters subsequent behavior. In a famous example that Kahneman covered, college students were given a short set of words and asked to make a sentence. Some of the students got words that evoke old age, like “Florida,” “bald,” “Bingo,” “gray,” or “forgetful.” The students were then sent down the hall for another activity — but the walk down the hall was the real test. The researchers reported that the students exposed to words associated with aging subsequently walked down the hall more slowly. This became known as the “Florida effect.”

Social priming research was hot for about a decade, starting in the late 1990s. All sorts of surprising effects were being reported, like that holding a warm beverage caused people to become more interpersonally warm.

But the year after Thinking, Fast and Slow came out, a group of researchers published a failed replication attempt of the Florida effect. It was just one of a barrage of failed replications in the field. As social priming came under scrutiny, Kahneman wrote an open letter to priming researchers. “I see a train wreck looming,” he warned. He urged them to confront the burgeoning problems head on, and transparently, and suggested next steps for figuring out whether or not the entire field was in peril.

Unfortunately, social priming research turned out to be the train wreck that Kahneman feared. Seemingly inconsequential interventions, it turns out, tend to have inconsequential effects, when they have any effects at all. One priming study after another unraveled, some due to fraud, and others just by failure to replicate. Today, that genre of priming research — in which an unwitting subject is exposed to a farfetched prod — is largely abandoned.

Given Kahneman’s stature, and the fact that his mega best selling book featured a chapter on priming research, he eventually (and fairly) drew some criticism from his peers. In 2017, three of them wrote a detailed blog post on the priming work covered in chapter four of Thinking, Fast and Slow, showing that the chapter was based on shaky studies.

What really stuck with me, though, was Kahneman’s response. Here was one of the most prominent public intellectuals in the world, posting in the comments:

“As pointed out in the blog, and earlier by Andrew Gelman, there is a special irony in my mistake because the first paper that Amos Tversky and I published was about the belief in the ‘law of small numbers,’ which allows researchers to trust the results of underpowered studies with unreasonably small samples…Our article was written in 1969 and published in 1971, but I failed to internalize its message.

My position when I wrote ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ was that if a large body of evidence published in reputable journals supports an initially implausible conclusion, then scientific norms require us to believe that conclusion. Implausibility is not sufficient to justify disbelief, and belief in well-supported scientific conclusions is not optional. This position still seems reasonable to me – it is why I think people should believe in climate change. But the argument only holds when all relevant results are published.”

Social priming results, it turned out, were too good to be true, and researchers simply weren’t publishing their failed results. It left a body of work that appeared consistently convincing. In his comment, Kahneman cited the complete absence of negative results from many small studies as a warning sign he should have recognized. He continued:

“Clearly, the experimental evidence for the ideas I presented in that chapter was significantly weaker than I believed when I wrote it. This was simply an error: I knew all I needed to know to moderate my enthusiasm for the surprising and elegant findings that I cited, but I did not think it through. When questions were later raised about the robustness of priming results I hoped that the authors of this research would rally to bolster their case by stronger evidence, but this did not happen…The lesson I have learned, however, is that authors who review a field should be wary of using memorable results of underpowered studies as evidence for their claims.”

Personally, I might have replaced the word “memorable” with “seemingly implausible,” because, as Uncle Ben should have told Peter Parker: “With claims of small interventions that cause large and surprising results comes great responsibility for great evidence.” (Common sense also matters. Non-scientists are actually decent at picking out which social science results will replicate just based on study descriptions.)

That aside, Kahneman’s forthright “the lesson I have learned” approach stuck with me in a very personal way. Here’s the thing about science writing: do it enough, and something you (and by “you” I mean “I”) write is going to turn out to be wrong. It’s inevitable. I think the instinct for most writers, due to the incurable condition of being human, is to hold fast to a conclusion simply because they’ve rendered it in ink. I struggled with that early in my career, but had to get over it to some extent to contradict one of my own favorite articles (which had won a journalism award) in my own first book. (I also slowly came to the conclusion that my masters thesis in environmental science had some statistical problems. But also some merit!)

I think I’ve gotten better about that, with the help of role models that include Kahneman. It seems appropriate that a man who changed how we think about thinking was also willing to change his own thinking. I’ll remember Kahneman as a brilliant man who was able to change his mind about things he’d written even after they’d become wildly popular.

A few years after the blog post, Kahneman said that, overall, the problems with replication (now known as the “replication crisis”) had been great for psychology, because it led to better work. Out of crisis came a “lessons I have learned” moment for the field. “In terms of methodological progress, this has been the best decade in my lifetime,” he said. He was a class act, whether he was changing all of our minds, or merely his own.

Thanks for reading. And thanks to everyone who commented on recent posts; there have been some excellent discussions in the comments. And special thanks to a few new subscribers who signed up for paid subscriptions. Thus far, I’ve used contributions for things like help transcribing Q&A interviews and licensing rights to a few photos.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

As always, you can subscribe here:

Until next time,

David

Loved this, David! A quote I heard from Jason Zweig WSJ, in his being gobsmacked about his conversations with Kahneman said something like ... "he has no sunk costs." If he's been working on something for a while and it turns out not to be the thing, or he has new information he has no problem giving up the ghost and moving on.

That's been incredibly helpful to me not just in business but in sports, relationships and in general living my life.

I want to be right. It's nice to be right. But I don't care about being right.

Great piece David, it reminds me of a Richard Dawkins story: "A formative influence on my undergraduate self was the response of a respected elder statesmen of the Oxford Zoology Department when an American visitor had just publicly disproved his favourite theory. The old man strode to the front of the lecture hall, shook the American warmly by the hand and declared in ringing, emotional tones: ‘My dear fellow, I wish to thank you. I have been wrong these fifteen years.’ And we clapped our hands red. Can you imagine a Government Minister being cheered in the House of Commons for a similar admission? “Resign, Resign” is a much more likely response!"