If you can only name two classical composers, I’m guessing they’re Beethoven and Mozart. And for good reason.

In addition to being two of the most impactful musical geniuses in history, they have dramatic personal stories. Beethoven composed grandiose symphonies while gradually losing his hearing. Mozart was the consummate prodigy who stunned his father when he played violin at their home with professional musicians despite never having had a lesson. Drama!

But survey composers and the most important musician is neither of those two.

When BBC Music Magazine asked 174 world-class composers to rank composers using a composite of originality, impact, and craftsmanship, the preeminent maestro was clear: Johann Sebastian Bach. His “spirit dwells in practically every note written since his death,” the magazine staff wrote.

When the chief music critic of the New York Times ranked historical composers, the top spot went to: Bach. Classic FM: Bach. Big Think: Bach. As 20th Century composer Mauricio Kagel put it: “Not all musicians believe in God, but they all believe in Johann Sebastian Bach.”

What fragments of his life are known, though, aren’t as dramatic as the Beethoven and Mozart stories. Here’s a lot of it: he was very religious; he spent much of his career as the musical director at St. Thomas Church, in Leipzig, Germany; he had 20 children (7 with his first wife before she died), only half of whom survived into adulthood. And along the way he laid a foundation for the future of music, Beethoven and Mozart included.

Last week, I was briefly in Leipzig, and took the opportunity to walk in the footsteps of Bach, and to visit the Bach Museum. Apart from the music he left, Bach’s life (including his musical process), isn’t very well documented. But I was struck by a quote in one of the museum’s exhibits, from a (translated) letter written by a theology student in 1741:

“You should know that the famous man who enjoys the greatest praise in our town in music, and the admiration of experts, isn’t able to delight others with the mingling of his musical tones until he has played a piece of written music and set his powers of imagination in motion. … This skillful man … has to play some written music which is inferior to his own ideas. Nevertheless, his superior ideas are the consequences of those inferior ones.”

According to the exhibit, Bach must have had extraordinary “mental agility,” because he seems to have composed movements of a piece in the correct sequence, with incredible complexity developing out of initial simplicity; he must have been holding a massive journey in his head. (He did, though, make frequent corrections along the way.) And he often did it very quickly. For years, he finished new pieces at least weekly.

Given Bach’s incredible genius, I found it especially interesting that he apparently played “lesser” music just to get his brain going, and to stimulate ideas that he would use for his own improvisation and composition.

This gets at a few creativity tactics I’ve been thinking about a lot lately:

Start with someone else’s stuff to get your own stuff going. I used to mistake originality for creativity. I didn’t want to be unduly influenced by other peoples’ work, so I eschewed a lot of it when I was trying to be creative. I was wrong! Having a lot of other peoples’ ideas in your head gives rise to new connections, which is the engine of creativity. After all, everything is a remix. (If you’re interested in this idea, I highly recommend one of my favorite newsletters, by artist Austin Kleon, author of the fantastic Steal Like an Artist.)

Start somewhere bad to get somewhere good. A few weeks ago, I interviewed psychologist Adam Alter about his book Anatomy of a Breakthrough. In it, he writes about the “creative cliff illusion,” the notion that good creative ideas will either come quickly or not at all. Unfortunately, our intuition has that one approximately backward. In studies of creative tasks — whether performed over minutes or days — the best ideas tend to come later. So don’t be discouraged if you aren’t a fount of creativity right out of the gate. Apparently neither was Bach.

Just have more ideas. Related to the point above, creativity research has found that eminent creators just generate more ideas — many of them not so great. (Again, Bach: a new cantata every week!) Thomas Edison held more than a thousand patents (and was rejected for many more), most completely unimportant. As I wrote in Range:

“His failures were legion, but his successes— the mass‑market light bulb, the phonograph, a precursor to the film projector—were earthshaking.”

Two of my favorite writers — Haruki Murakami and Martin McDonagh — have written some of the best and worst stuff I’ve ever read. One of my favorite artists, sculptor Rachel Whiteread, was the first woman ever to win the Turner Prize — a British award for the best artistic production of the year— and also the “Anti‑Turner Prizer” for the worst British artist. And she won them in the same year. Creativity is high variance, and your best ideas probably don’t come right away. Isabel Allende, one of my favorite writers (and people), told me recently that she sometimes spends weeks at the start of a new novel writing with little or no editing just to get going, knowing that none of that early work may end up in the book.

In Anatomy of a Breakthrough, Alter writes that Jeff Tweedy, singer and guitarist of Wilco, intentionally lowers his standards when he’s stuck, and just pours out bad ideas until he can get to good ones. As Tweedy told Ezra Klein:

“To avoid writer’s block I write through songs that I don’t like. I get an idea for a song, I just go ahead and do it, even though I don’t think I’m going to like it. And I feel like that frees me up to go to the next song.”

It’s no secret that persistence is important, but perhaps we don’t associate it with creative output as much as we should. So don’t mistake originality for creativity — it’s fine to do a Bach and start with someone else’s work to get yourself going — and lower the bar for your early ideas, since you shouldn’t expect the best stuff to come first.

I plan to write more about these and associated ideas, but I’d love to read comments below the post on how you get into a creative groove, or just a thought of something you might try in the future. Last post, I asked for comments from readers about the note-taking systems they employ in order to keep good ideas from getting away; the responses were fantastic! Thank you to everyone who shared a thought.

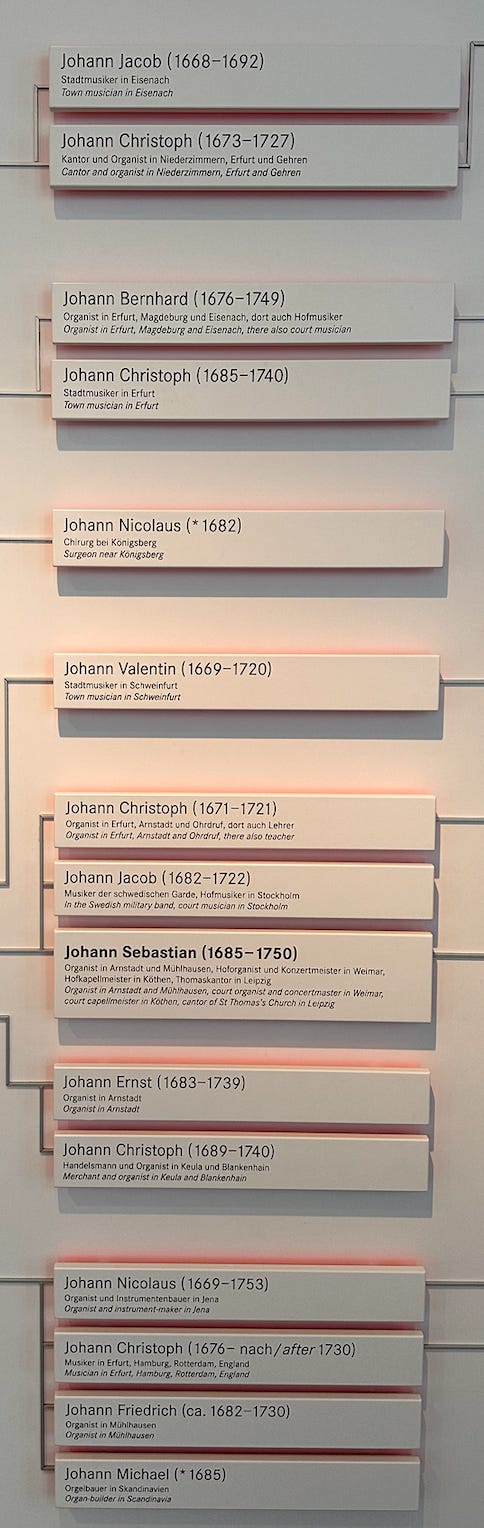

Bonus fact: I learned at the museum that the Bach family loved the name Johann even more than George Foreman loves the name George. Behold Johann Sebastian’s generation of the family tree.

Want to guess the name of Bach’s first son? ….Wilhelm! Although a number of his other sons were named Johann. In fairness, naming norms weren’t the same as they are now, and many 17th and 18th century Germans went by their middle names. Glad we got that cleared up.

One final Bach tidbit: Bach has three pieces on the “Voyager Golden Record,” which was sent into space with the Voyager spacecraft in 1977. Beethoven has two, and no other musician has more than one. So if aliens find the record, Bach is our musical emissary.

Thank you, as always, for reading.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it.

You can also support Range Widely’s continued existence with a free or (voluntary) paid subscription.

Until next time…

David

I have found that playing Bach on the piano is like having someone gently pressure-wash your brain — your thoughts feel clear and clean and beautiful!!

The blog post nicely illustrates how and why interacting with a chatbot can be useful. The chatbot can generate a range of ideas, many of them bad, and can also iterate on the early ideas you might give the chatbot. None of the ideas or feedback generated by the chatbot might end up in your final creative output, but it can be an effective and cheap partner early on in the process. Ethan Mollick has written a blog post about this: https://www.oneusefulthing.org/p/the-practical-guide-to-using-ai-to