“My dad threw me into every sport you could imagine.”

A great study of athletic development tells a familiar (albeit unpopular) story

Having explained my misfire of a newsletter launch last week, I was planning to follow that up with an end-of-summer themed post about a hallucinogenic, parasitic fungus that commandeers cicada brains.

Alas, that wholesome fun will have to wait a week, because a teenager won the U.S. Open.

The Background

Earlier this month, 18-year-old British tennis player Emma Raducanu won her first Grand Slam title. It was a shock; she entered the tournament with 400-to-1 odds. One of my favorite sportswriters, the Guardian’s Sean Ingle, asked Raducanu’s former coach about the factors that helped her talent blossom. Here’s what the coach said:

“From my perspective one of the best things with Emma is that she was exposed to a lot of sports from a young age, and didn’t go too specific into tennis straight away. I see that on court. When she’s learning a new skill, or trying something a little bit different, she has the ability and coordination to pick things up very quickly, even if it’s quite a big technical change.”

Raducanu added this:

“I was initially in ballet, then my dad hijacked me from ballet and threw me into every sport you could imagine. I was doing horse riding, swimming, tap dancing, basketball, skiing, golf and, from the age of five to eight, I was go-karting…From the age of nine I started motocross in a forest somewhere for a year. This was all alongside tennis.”

The introduction to my book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, begins with an examination of athletic development, initially through the contrasting stories of Tiger Woods (at 2, he was on national TV showing off his swing), and Roger Federer, who had a far less famous, and far more Raducanu-esque upbringing.

Both men reached the pinnacle of their respective fields. But while Tiger's story is far more renowned, (as my friend Malcolm Gladwell said, the TV clip of 2-year-old Tiger is practically “a human cat video”), the Roger path turns out to be the typical one.

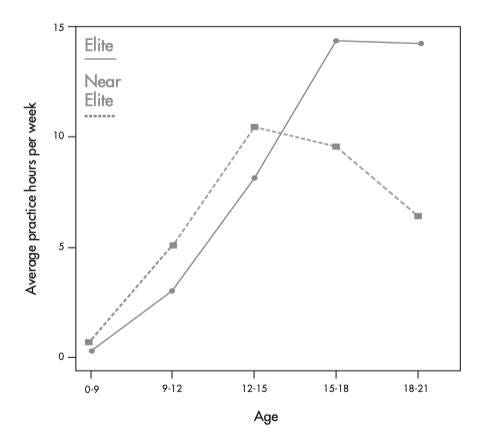

Below, for example, is a graph I put in the Range intro that plots data from a study of athletic development. The study found that future elites tended to spend less time early on (compared to lower-level peers) practicing in the sport in which they would become elite. Future elites tend to have a “sampling period,” where they engage in a variety of physical activities before focusing.

So What’s the Controversy?

The research obviously persuaded me, but I have learned that it does not persuade everyone. And I get it. In addition to featuring a human cat video, the Tiger story is ridiculously dramatic — and intuitive.

Every time a story like Emma Raducanu’s makes headlines, I get a flurry of messages – from both colorful sides of the “You're a genius!”/”You’re a clown!” aisle. This time around, one Twitter guy suggested that pointing out Raducanu’s developmental path was just virtue signaling nonsense. Multisport as virtue signaling...that was a new one by me.

I have a no-arguing-on-Twitter policy (highly recommend), but I am happy to share a brief thought or highlight relevant research. In this case, there happens to be a brand new paper by a trio of scientists from the U.S. and Germany that perfectly fits the bill.

“What Makes a Champion?”

In the intro to their paper, the three scientists nod to popular books (including mine and Gladwell’s) that have helped spur interest in research on the development of exceptional performance. Then they analyze 20 years worth of studies on athletic development. Spoiler alert, here’s the title of the paper: “What Makes a Champion? Early Multidisciplinary Practice, Not Early Specialization, Predicts World-Class Performance.”

This is not a surprise to anyone who has been following this area of research closely. In the Range endnotes, I have more than a full page (in really tiny print!) of citations from different sports and countries that reach broadly similar conclusions. Nonetheless, I think this particular paper deserves extra attention for two reasons.

First: it’s really well done. The researchers aggregated the results of 51 study reports from around the world. That included data on 6,096 athletes, ranging from those who competed at a local level, all the way up to 209 gold medalists. The results — that the best athletes more often had a sampling period — were consistent across a variety of sports.

Second: the researchers delved deeply into a question that I find endlessly fascinating: Does a head start predict ultimate achievement?

I think human intuition is such that we reflexively judge potential based on achievement that we see right now. In other words, if we see Jasmine and Kimberly compete in X activity, and Jasmine is 20% better, our instinct is that Jasmine will always be 20% better, as if human development unfolds on a linear trajectory. But it doesn’t, which is a theme of Range.

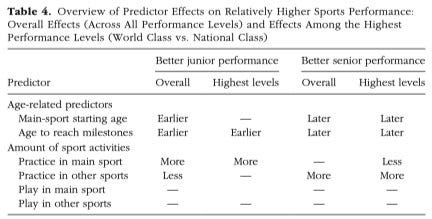

In this new paper, the scientists separately examined the developmental predictors of success for junior (i.e. youth) versus senior level athletes, which allowed them to get at the question of whether early success predicted later elite performance. The table below summarizes their findings:

The predictors of youth success were opposite to those of adult success. The best youth athletes tended to start and specialize in their main sport earlier, and they reached performance milestones (like competing in a national championship) earlier.

Meanwhile, here are the scientists describing the best adults:

“Senior world-class performers engaged in more coach-led practice in sports other than their main sport during childhood/adolescence and, relatedly, began playing their main sport later, accumulated less main-sport practice, and reached performance milestones at a slower rate than national-class performers. That is, senior world-class athletes who began their main sport early and specialized are the exception, not the rule.”

If the goal is to win the 10-year-olds’ championship, then early specialization seems to make sense. If the goal is to develop the best 20 or 30-year-olds, then not so much. As the researchers write, talent development programs that specialize youth athletes early may “reinforce rapid junior success at the expense of long-term senior success.”

Why Does It Work That Way?

The researchers offer three hypotheses consistent with the data:

Multisport development makes young athletes more resistant to physical injury and psychological burnout. (Cirque du Soleil physiologists once told me that they slashed injury rates by having acrobats learn the basics of other performers’ disciplines.)

Trying more sports and delaying specialization improves the chances of high match quality between the athlete and sport. (Or, as I like to say: the fewer things they try and the earlier you force them to choose, the more likely you are to get the wrong person in the wrong spot.)

More varied learning early in development makes for better learners later. (This is what Raducanu’s coach was expressing in the quote at the top of this post.)

Personally, I think the totality of evidence in this area of work suggests all three of these factors at play. That said, I think it’s important to remember that individual development is tremendously variable. There is no one-size-fits-all plan, and I think we should diversify development pipelines accordingly.

As Chelsea Warr, who helped design the UK Sport talent development systems that led to huge success in the 2012 and 2016 Olympics, once told me: “We want to make room for the ‘fast risers’ and the ‘slow bakers’.”

The problem, I think, is that typically (and not just in sports), we focus only on the fast risers, even though the research says that they are the exception, not the norm. This relates to something I confessed recently: that the subtitle of my own book in my head differs from the one actually on the cover.

To me, the ubiquitous theme of the research that went into Range was: sometimes what works best for short-term progress actually undermines long-term development — whether the goal is learning a skill, choosing a course of study, or developing in your career. (As you might imagine, a 28-word subtitle wouldn’t cut it;) In other words: optimal development often looks, at first, like falling behind.

David’s Digressions

-The study featured in today’s post reminded me of a conversation I was very fortunate to have with Serena Williams in the fall of 2019. She told me that, as a child, she participated in ballet, gymnastics, taekwondo, track and field, and that she and Venus threw a football to develop the motion for a powerful serve. Despite having been a senior writer at Sports Illustrated, and having written a book about the benefits of breadth, I’d never heard that! The “Tiger stories” seem to be culturally stickier, even when they aren’t true.

-My brother sent me this LeBron James tweet:

I’m not sure exactly what he’s referring to, and it seems like he’s probably subtweeting someone. And, of course, LeBron trains in all sorts of ways that are different from what he'll do on the court. But it reminded me of another reason why athletes might practice moves they don’t intend to execute — durability. To expand on a short point above: I’ve interviewed physiologists who worked with Cirque du Soleil, and learned that they started a program in which developing performers would learn some of the basics of disciplines outside their own speciality — not in order to perform them, but to see if there would be a durability benefit. It led to a massive decline in injuries.

-Finally, one of the responses I saw repeatedly to Sean Ingle’s Guardian piece about Emma Raducanu was that it’s unfortunate that pay-for-play leagues make it increasingly hard for all kids to have a multisport experience. I share that concern. If you’re interested in a different model, check out the HBO Real Sports episode on youth sports in Norway. Norway is an insanely good sports country. The population of Norway is something like the metropolitan area of Boston, and the country won the most medals at the last Winter Olympics, and did quite well this summer. (They won gold in men’s beach volleyball. Who knew?!?) As the HBO segment shows, youth sports in Norway are cheap and accessible. Also: there’s a national ban on ranking child athletes before age 12.

Thanks for reading. Until next week…

David

By age 6 Federer himself states, he was playing tennis "all he time." He says, "I could never really get enough. I played with my parents, friends and whoever wanted to play with me at the tennis club. If there was no one to play with I would spend hours smacking tennis balls against the tennis wall." By age 9 he's getting private lessons. And in the research article you reference they use Federer as an example of not specializing early. I supposed practicing "all the time" at age 6 is not early enough for some to think that specialization does not matter. But, 6 seems pretty early to me. The article you cited also used Gretzky. Yet, Gretzky was playing hockey at two and a half years old. I supposed he could have started at 6 months old but 2 and half seems pretty early to start learning the game. It also cites Michael Phelps. He started when he was 7 and had a national record by 10 and was training with Bob Bowman by age 10. This all seems pretty early to me.