Missing the Burning Forest for the Trees

When the chain of communication and chain of command are the same, it's a recipe for disaster

Welcome to Range Widely — the newsletter for generalists, where I'll help you step outside your lane for a few minutes each week. You can subscribe here:

If you left a comment on a previous post, I've probably replied.

“Officials just lie about the scale of it, that is, they willfully misrepresent the data, because every official is responsible for making sure there is a beautiful picture.”

That quote, in a Washington Post article about the massive wildfires in Siberia this summer, caught my eye. The speaker is Alexei Yaroshenko, a Russian forestry expert; he’s explaining that even though drones reveal the incredible scale of the destruction, (the Siberian fires were larger than the rest of the world’s combined), local officials lie about the extent of damage in their own area. Those local officials, Yaroshenko says, just have a long-standing habit of fudging statistics so they don’t get in trouble with their superiors in Moscow.

The issue is compounded by the fact that state media, doing its own part to paint a rosy picture, report on the fires that have been put out, not the ones still burning. Among the disastrous outcomes of the chain of obfuscation: small farmers in Siberia are still setting fires to clear land, unaware that they may unwittingly contribute to a catastrophe. They are, one might say, missing the burning forest for the trees.

The Post article reminded me of a topic that — like Fermi estimation — I expect will come up repeatedly here in RW: the importance of differentiating the chain of communication and the chain of command.

This concept is important for a number of reasons, one of which is to ensure that managers (or bosses in Moscow) aren’t getting information only from people whose main concern is earning their approval, or at least not ruining their day. As Rex Geveden, formerly the chief engineer and associate administrator of NASA, once told me: “The chain of communication has to be informal, completely different from the chain of command.”

Early in his time at NASA, before he was the chief engineer, Geveden became aware that when the chain of communication and chain of command became one and the same, engineers stopped raising problems to their bosses. And even when they did raise alarms, their superiors tended not to relay that up to their own bosses. At each level of the chain of command, concerns were diluted, or scuttled entirely, until information simply stopped flowing. There was a lack of “healthy tension,” as Geveden put it.

This culminated for NASA in 2003, when engineers concerned about a technical problem took initiative to ask the Department of Defense for high-resolution photos of a part of the space shuttle Columbia they thought was damaged. Not only did their managers block outside assistance, but they apologized to DoD for contact outside “proper channels,” and promised it wouldn’t happen again. That was the end of that outside-the-chain-of-command request for information. The shuttle, which was indeed damaged, exploded upon reentry.

When concerns and bad news don’t have informal channels to flow through in an organization, Geveden observed, they flow more slowly, or they stop flowing entirely. Communication becomes viscous. It hadn’t always been that way at NASA.

"Monday Notes"

When Wernher von Braun led the Marshall Space Flight Center and development of the Saturn V rocket — which first propelled humans to the moon — he implemented a system that proactively differentiated the chain of communication and chain of command. It was called, “Monday Notes.”

At the end of each week, engineering teams submitted a single page of notes on their salient issues. Those could be problems, triumphs, unexpected findings, information that might help another team, requests for assistance, whatever. Occasionally, they raised social issues of the day.

Von Braun took the notes and put handwritten comments in the margin. Sometimes he broke out exclamation points to congratulate a team; other times he left a raised-eyebrow question mark (like on a page that read: “Nothing of significance to report.”). He asked for clarification when he didn’t understand something, and he solicited disagreement. When he wanted an extra opinion on an issue in the notes, he wrote a specific engineer’s name alongside “Please comment!”

Importantly, on Monday, all of the notes — with his handwritten comments — were recirculated to every team. Everyone could see what others were up to, and they could see that raising problems and being transparent about confusion was met with helpful suggestions from the big boss. Nobody had to play the role of the first person to raise their hand at an all-team meeting.

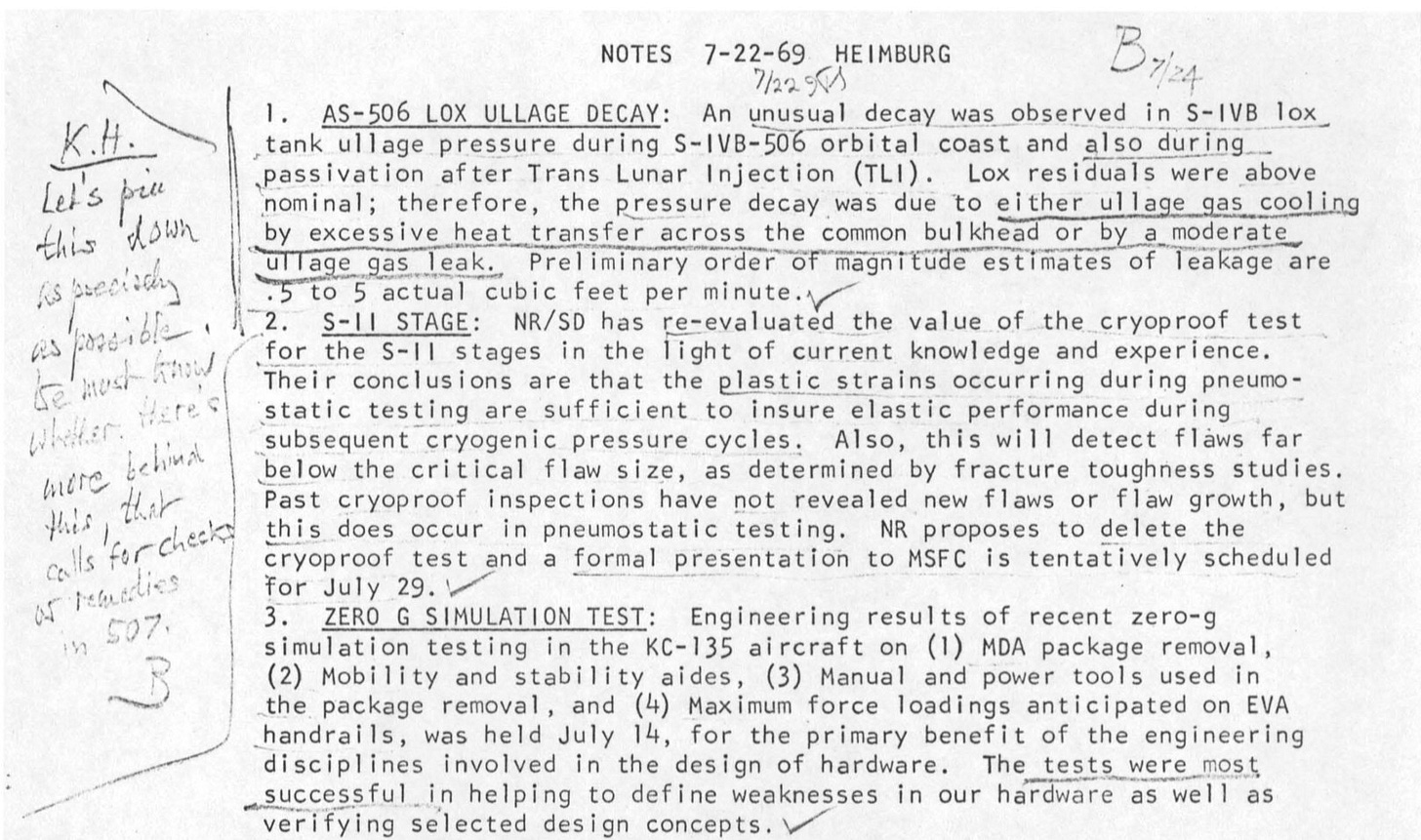

"Monday Notes" were a constant, no matter what else was going on. Here's a page from two days after the Moon landing. At top, an engineer shares data about a liquid oxygen tank that unexpectedly lost pressure. It was already irrelevant for the Moon mission, but it could impact future flights; so von Braun, in his note, is making sure they don’t ignore it. Communicating problems before they were urgent was a staple of Monday Notes.

In 1974, William Lucas took over as head of the Marshall Space Flight Center. A NASA chief historian later wrote that Lucas was a brilliant engineer, but “whereas von Braun sought out problems and rewarded those that brought problems into the open, Lucas often grew angry when he learned of problems, with a ‘shoot the messenger’ attitude.”

Lucas transformed von Braun’s Monday Notes into a system purely for upward communication. He did not write feedback, and the notes did not circulate. Eventually, they became standardized forms that had to be filled out. “Immediately, the quality of the notes fell,” wrote another official NASA historian. The chain of communication and the chain of command came into unfortunate alignment, which contributed to the Challenger explosion in 1986.

The Challenger investigation board made clear that NASA culture had been suffering from a serious communication gap between engineers and managers. Information was not flowing freely. Nearly two decades later, the Columbia investigation board would find that, again, a rigid chain of command and lack of informal communication meant that problems weren’t raised until it was too late.

Chain of Communication ≠ Chain of Command

In 2017, Rex Geveden — the former NASA chief engineer — took those lessons to his new role as CEO of nuclear technology company BWX Technologies. Some of BWX Technologies’ managers are retired military leaders, used to a strict chain of command. That’s fine, he told them, but it has to be differentiated from the chain of communication.

Geveden wrote a memo sharing his expectations. “I warned them, I’m going to communicate with all levels of the organization down to the shop floor, and you can’t feel suspicious or paranoid about that,” he told me. “I told them I will not intercept your decisions that belong in your chain of command, but I will give and receive information anywhere in the organization, at any time. I just can’t get enough understanding of the organization from listening to the voices at the top.”

I think it’s especially important right now to be proactive about differentiating the chain of communication and chain of command. Some degree of remote work is here to stay, so we can’t count on the proverbial water cooler as a hub of informal communication. I don’t think that means we can’t differentiate the chain of communication and chain of command effectively, but I do think it means we'll have to be more systematic about it.

If you're doing more remote work these days, has it impacted informal culture, or the flow of communication in your domain? If so, what could be your version of Monday Notes? If you have an observation or suggestion, leave it in the comments!

David’s Digressions

-If you want to read a bit more about Monday Notes, check out this post from a former NASA chief historian. And if you want more about differentiating the chain of communication from the chain of command, that topic is at the heart of chapter 11 of Range.

-This post reminded me of my friend Safi Bahcall’s book, Loonshots. Safi describes how organizations (especially growing ones) often go through a “phase change” in which a culture reorients from one in which everyone is working for the survival of the whole, to a situation where everyone is working to protect their own turf — even if that’s at odds with the survival of the whole. Think: local officials reporting on Siberian wildfires.

-Further afield, this reminded me of a novel you may have heard about... what's it called again — oh yeah War and Peace. (That link is to my favorite translation, but not the most popular one; I’ve heard complaints about Britishisms. Whatever, it’s majestic. YMMV.) In the book, which includes Tolstoy’s historical reporting, the chains of communication and command are so aligned in the French army that by the time Napoleon gets news from the battlefield, the information is irrelevant, which leads him to issue irrelevant commands, which are thus ignored at the front, and the cycle of irrelevance repeats. It doesn't work out super well for him.

Thank you for reading. Until next time...

David

p.s. If you liked today’s post, please share it! You can find it (and other posts) here.