Here’s Why Coverage of the Cash-Improves-Baby-Brains Study is Misleading

If you know what to look for, the tantalizing new report doesn't look as great

Welcome to Range Widely, where I hope to help you think new thoughts. If you aren’t subscribed, you can do that here:

Last week, I wrote about how everything in your fridge causes and prevents cancer, and how health research should be interpreted with caution. The bottom line was that when researchers have many opportunities to slice and dice a large dataset, it becomes easy to generate spurious correlations; the most interesting spurious correlations then tend to end up in scientific papers and the subsequent press releases.

This week, I’d like to share some pretty serious cautionary notes about an absolutely tantalizing new study that made major headlines — and that I very much hope is completely true! Let’s begin…

The Study

How about I just share the first paragraph of the New York Times coverage of the new study:

A study that provided poor mothers with cash stipends for the first year of their children’s lives appears to have changed the babies’ brain activity in ways associated with stronger cognitive development, a finding with potential implications for safety net policy.

Well! I think we can all see why this is a big deal. The researchers don’t yet claim to know why they found these results — whether mothers were able to get better food, or healthcare, or spend more time with their kids, or something entirely different — but scientists quoted in the Times article called the work groundbreaking, and the first of its kind in showing “that money, in and of itself, has a causal impact on brain development.”

Here’s how the study worked: mother/newborn pairs were randomized to receive either $333 a month or $20 a month. The families had an average income below $20,000, so the larger payment was a substantial boost, and could be spent however the mothers wanted. When the babies turned one, researchers administered electroencephalograms, which measure electrical activity in the brain. They reported that the babies of mothers who got the higher payment had more of a certain type of brain activity.

Reasons to Be Cautious

Let me first say that I find this result exciting, and if it is what it purports to be, and it holds up (the study will run at least until the children are four), I certainly think it should have major policy implications. But I want to highlight two reasons to be cautious. The first, short and straightforward. The second, more worrisome, and requiring more explanation.

First: electrical activity in the brain is a proxy for what the scientists actually care about — brain development and cognitive abilities that lead to better life outcomes. The researchers saw more of a certain kind of high-frequency electrical activity in the brains of one-year-olds in the high-payment group. The question, then, is whether that electrical activity is a good proxy of later development. As a Vox article covering the study noted, this type of brain activity has been correlated to language and memory abilities in older kids in other studies. But we really don’t know what this means for one-year-olds. I think the major news coverage did a reasonable job of pointing out that electrical activity in the brain, in and of itself, isn’t the dependent variable we really care about. Now, on to the big one…

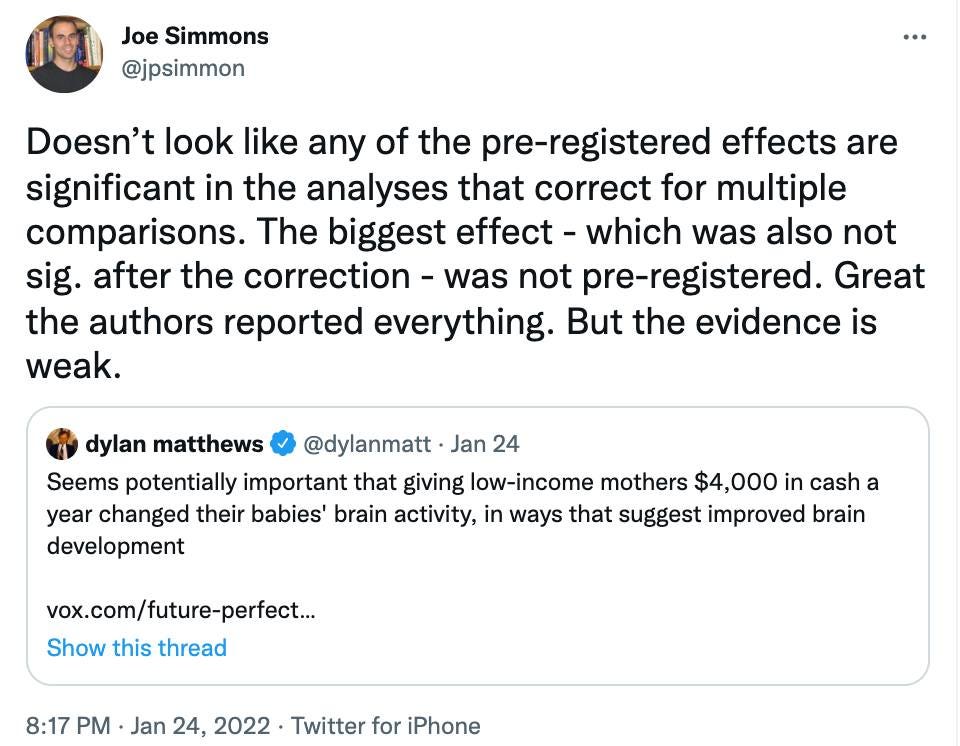

Second: Wharton professor Joe Simmons (among others) made a point that entirely escaped the news coverage I read, perhaps because it’s more esoteric. Or perhaps because it might have curtailed the news coverage altogether:

What is Prof. Simmons Talking About?

Let’s zoom in on his point about “pre-registered effects,” because this dovetails with last week’s post. Bear with me for a few paragraphs, because I need to explain pre-registration — and it’s an important issue for thinking about scientific research in general.

Last week, I wrote about how scientists can alight on false-positive findings just by chance when there are many “researcher degrees of freedom” — or ways in which the scientists can group and analyze their data. Since there are many false positive correlations waiting to be found in any large data set, having freedom to slice and dice the data at your whim helps ensure you’ll find some of those false positives.

“Pre-registration” is an increasingly common tactic that scientists use to reduce the amount of freedom they have. (“Pre-registration: When you want less freedom.” Not going to win an election campaign, is it?) Specifically, when scientists pre-register a hypothesis, it means that before the study begins they specify what effects they will look for when they do their data analysis later on. In other words, they can’t just go plunging through their data looking for any old positive correlation and claiming to have predicted it, because they told their peers ahead of time what they would look for.

Last week, I used the hypothetical example of a football commentator who says that the Chicago Bears are undefeated after a bye week when they wear their alternate jerseys. When you look at the past, sifting data for stats like that is easy; they abound just by chance. If the commentator instead predicted that the Bears would henceforth go undefeated after bye weeks while wearing alternate jerseys, and the commentator was right, then that commentator might really be on to something. It could still be luck, but it’s more likely the commentator uncovered some real cause and effect.

Intuitively, you probably get this, in a way. You’d probably be more amazed if a commentator predicted an effect and turned out to be right than if the commentator told you about the past and assured you it could predict the future.

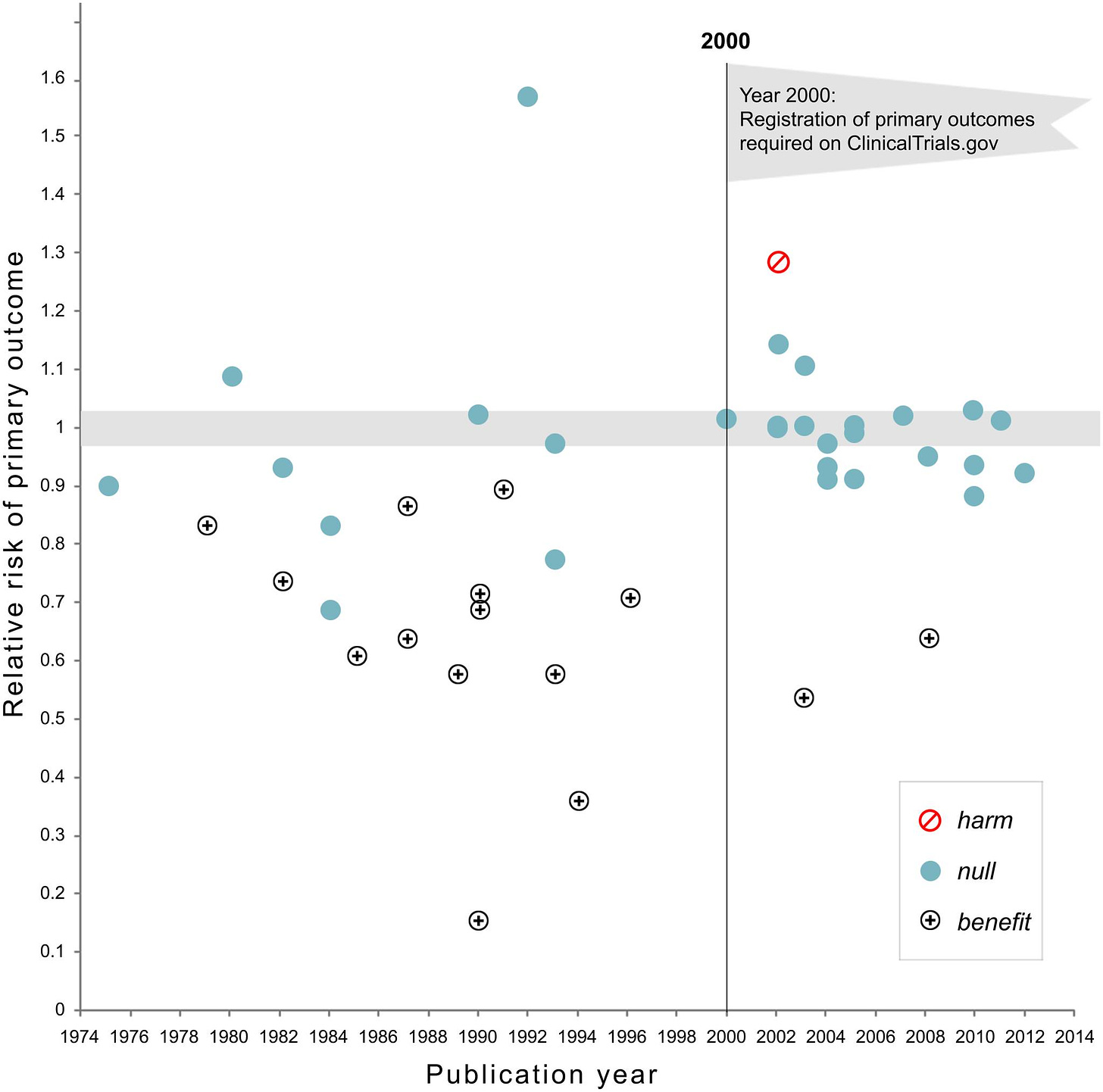

Turns out, when clinical trials have pre-registered hypotheses, they tend to produce a lot fewer positive results. Take a look at the figure below, from a 2015 study of drug and supplement trials for cardiovascular disease. Each circle on the chart is a single drug or supplement trial, and the x-axis shows the year the trial was done. The circles with a plus sign are trials that found a beneficial effect of the drug or supplement; the solid blue circles are trials that found no effect.

Drugs and supplements seemed to work a lot better prior to 2000! Y2K drug trial bug?? No. That’s the year that the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute began insisting that researchers it funded pre-register the effect they were planning to study. Again, that meant that the scientists had to specify before the study if, say, their plan was to see whether a drug prevented heart attacks in women over the age of 60; they couldn’t just collect data and then retrospectively look for positive correlations.

As you can see, when researchers have to specify ahead of time what they’re looking for, they’re a lot less likely to report back with positive results.

Getting back to Prof. Simmons’s tweet, he’s saying that the largest effect of payments on brain activity in this new study was not pre-registered, and thus we should treat it with caution. Furthermore, he’s also saying that the effects that were pre-registered were found not to be statistically significant. Raise the caution flag. Effects that the scientists specified in advance were not found, while the most headline-worthy one was not specified in advance.

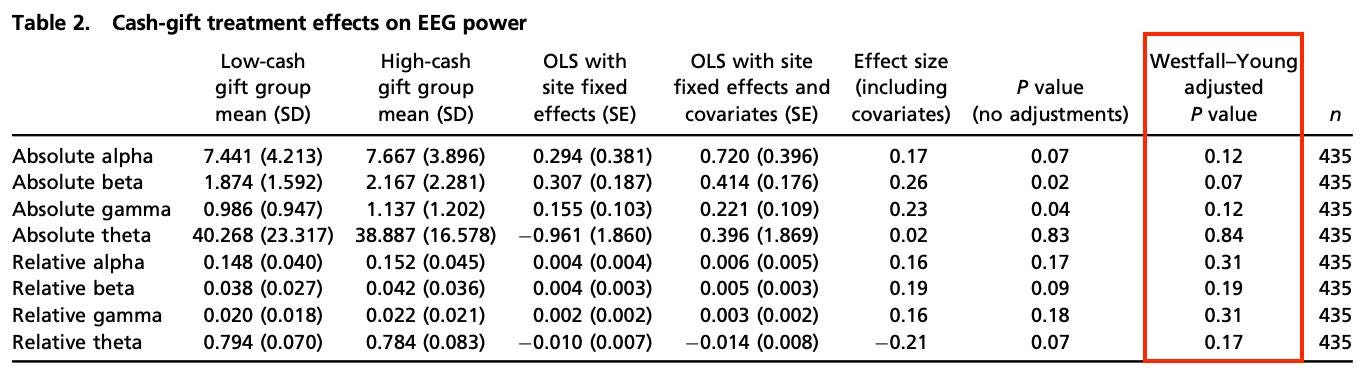

In fact, looking at the actual study results — below, showing different types of brainwaves — once appropriate statistical corrections were made, none of the results meet the traditional standard to be considered “statistically significant.” None of them. “The results are interesting, but none were statistically significant” is a far cry from the national headlines that are now collected on the study’s official site.

The traditional standard for statistical significance — a measure of how likely a result would have been to occur by random chance — is a P value of less than 0.05. None of the results met that threshold. The one that was closest (absolute beta) was not preregistered.

This does not mean that the results are certainly false. And, as Simmons notes in the very next tweet, “I do think that giving (enough) cash to poor mothers is very likely to have beneficial behavioral and developmental effects."

What Does This Mean For The Study?

Overall, the “Baby’s First Years” study is a momentous and important effort. I agree with Simmons; I think cash payments above a certain threshold are likely to have a host of beneficial effects on children, whether or not those have to do with infant brainwaves.

I’m also eager to follow the study. But the results published so far are not, in fact, strong evidence of the headlines, or of scientists’ claims in news articles.

The good news is that the scientists went out of their way to be transparent. They openly shared their data, and the process of their analysis, in addition to pre-registering their hypotheses. (For more info on their brainwave-analysis pre-registration, see section SI4 here. And to see other effects they'll examine, see this.) The reason that it's easy to critique their work quickly is because they openly shared how it was done, allowing others to work with the data. Kudos to them! The bad news is that the news coverage, including the scientists’ own quotes, will leave readers with an unfairly definitive conclusion.

Thank you for reading. If you found this post useful, and would like me to keep writing on science news from time to time, please share it.

I’ve realized that reader shares are really the only way that this newsletter spreads. And if a friend sent this to you, you can subscribe.

Until next week...

David